The only census of attendance at religious worship ever taken in England and Wales was on Sunday 30th March 1851. The same date as the full census for the entire population. The returns for this religious census were collected and examined by a local census officer. They survive today as a fascinating insight into religious observation in the middle of the nineteenth century.

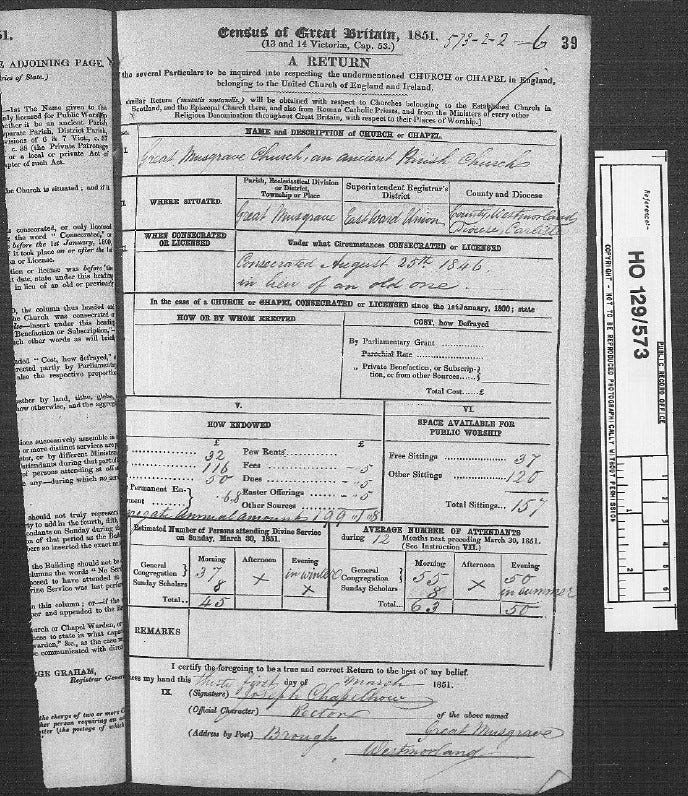

The ‘Ecclesiastical Census’ returns provide detailed information, by parish, on the place of worship for each religious denomination. The returns record the sittings available, the number of people attending any services during that day and the estimated attendances and average numbers during the previous twelve months. The returns also record the number of children attending Sunday School and often the foundation date of a particular meeting or place of worship, as well as any endowments.

Entry for Great Musgrave parish church, Westmorland, Ecclesiastical Census Returns [TNA HO 129/573/39, 1851]. Image copyright of The National Archives. Not to be reproduced without permission.

The census tells us a great deal. Many small groups met outside of official buildings such as in cottages, barns, and workshops. It is clear from the returns that well over half of the population did not attend any form of religious service on the day the census was taken. In some industrial cities, this proportion was as little as one in ten. Around half of those who did attend a religious service attended a nonconformist meeting. In some areas, such as Yorkshire’s West Riding, the proportion of nonconformists was much higher.

Despite its usefulness to the researcher, there are downsides to the census. Problems of interpretation and limitations on what information was recorded are apparent. There is no indication of how many people attended more than one service during that day, so we cannot determine the number of people attending each congregation or religious attendance overall. Often, people attended multiple times during the day, even visiting different denominations. Some Anglican vicars refused to participate in the census on the grounds that they believed the state had no right to enquire into such matters. However, these issues do not detract from the usefulness of the census in establishing the relative strength of different religious denominations. It is generally accepted that these returns were made conscientiously and that in general, they are fairly accurate.

The returns are held by The National Archives under the reference HO 129. Some have been printed. In recent years these excellent records have been made available online. The returns can be searched and downloaded: Home Office: Ecclesiastical Census Returns.

References and Resources:

Information for this post was taken from the excellent David Hey (ed.), The Oxford Companion to Local and Family History (1996), 142-3.

For examples of printed versions of the returns see; Kate Tiller (ed), Church and Chapel in Oxfordshire, 1851: The Return of the Census of Religious Worship (1987), R.W. Ambler, (ed), ‘Lincolnshire Returns of the Census of Religious Worship, 1851’, Lincoln Record Society, 54 (1975)

Alan Everitt, The Pattern of Rural Dissent: The Nineteenth Century (1972)

D.M. Thompson, ‘The Religious Census of 1851’ in R. Lawton (ed), The Census and Social Structure: An Interpretative Guide to Nineteenth-Century Censuses for England and Wales (1978)

Good post!

But I was wondering if you could write an article about the history of European mythology such as King Arthur and such?