Bills of Mortality

London

The Bill of Mortality is of very great use and necessity, and therefore not to be slighted, since it so much conduceth to the Health of the City, and Preservation of the Members thereof, in that it giveth a general notice of the Plague, and a particular Accompt of the places which are therewith infected, to the end such places may be shunned and avoided.[1]

Bills of Mortality were first used in London in the late sixteenth century then continuously from 1603. They were created to list christenings, burials, and causes of death. In 1611 the Worshipful Company of Parish Clerks were tasked with recording the statistics reported to them every week by parish clerks who in turn received their information from the searchers, a group of (mostly) women hired by the parishes of London to determine cause of death. The Bills of Mortality were published weekly on single sheets of paper. Annual returns were due on 21 December. The practice came to be copied in other urban centres like Norwich.

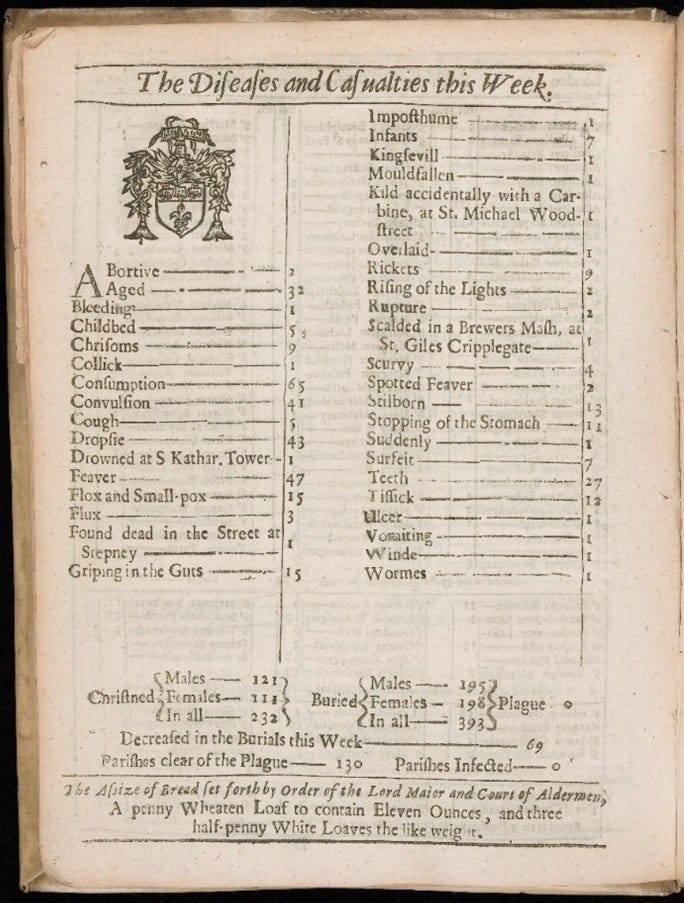

London’s Dreadful Visitation: Or, A Collection of All the Bills of Mortality For this Present Year (1665). Wellcome Collection. (CC BY 4.0)

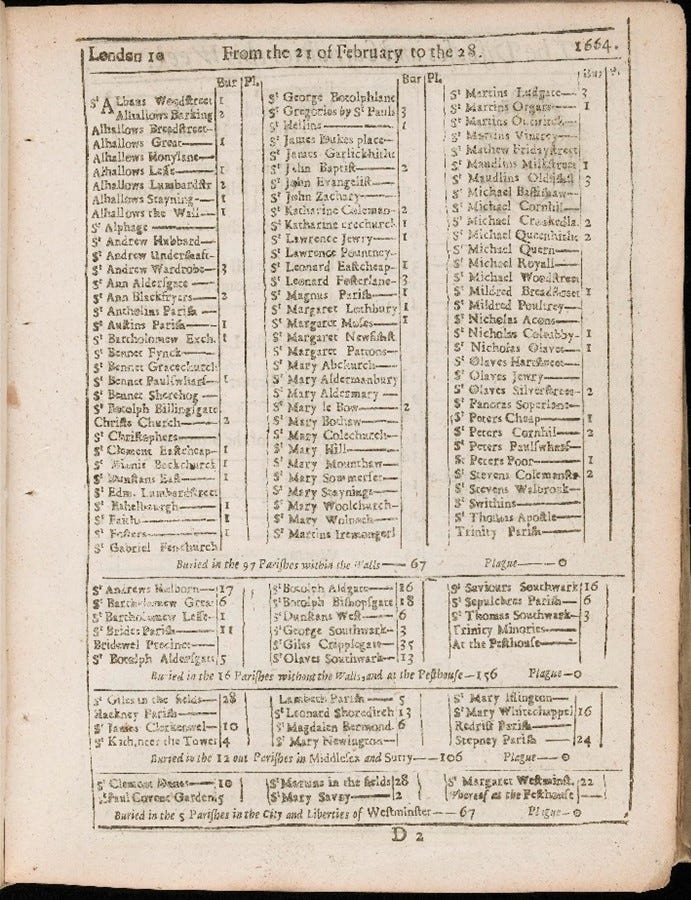

On the single sheet weekly Bills, one side listed the number of burials by parish, and, by the middle of the seventeenth century, the reverse recorded a summary account of the causes of death. This was titled ‘The Disease and Casualties this Week’. Some of the causes of death listed are familiar to us today, others leave a little more to ponder. For example, Planet/Plannet or Planet-shot, where an individual was thought maligned by the forces of the planets. They had probably been stricken by aneurisms, strokes, or heart failure. The Bills appear to have been widely read and commented upon and therefore ‘the Bills became a complex hybrid of commercial news service, public health measure, and scientific publication’.[2]

Bill of Mortality for Week Commencing 21 February 1664. Wellcome Collection. (CC BY 4.0)

It is due to the Bills of Mortality that surveys of London have been conducted by demographers such as John Landers and E. A. Wrigley and Roger Schofield and their momentous study The Population History of England 1541-1871 (1981). Landers’ book Death and the Metropolis: Studies in the Demographic History of London 1670-1830 (1993) provides a statistical analysis of the weekly and monthly Bills of Mortality, parish registers, and two Quaker houses.

The Bills are reliable records of parochial burials, but not necessarily of deaths.[3] However, even making allowances for the discrepancies within the Bills and the data omitted, it is possible to surmise that the population of London grew rapidly from roughly 200,000 in 1600 to at least 350,000 in the 1650s and to over half a million by 1700. By the 1750s approximately 675,000 people filled the metropolis.[4]

The Bills of Mortality were read far beyond London and beyond the British Isles but were, of course, popular items to collect in the city. Pepys recorded the numbers in his diary and Daniel Defoe used them for his 1722 novel A Journal of the Plague Year.[5] The Bills tell the London historian about the population, the seasonality of certain diseases, the makeup of different parishes, and the odd and surprising deaths that occurred throughout the metropolis. The Bills declined from 1819 and the last surviving weekly bill dates from 1858.

Many Bills can be accessed online through a Collection of Yearly Bills of Mortality, from 1657 to 1758 Inclusive. Some libraries have microfiche copies from 1700 onwards and there are physical copies in archives such as the Wellcome Institute, Guildhall Library, and London Metropolitan Archives.

References and Resources:

There are many sources with which to learn more, in addition to the specific resources mentioned throughout this post. An excellent site is The Bills of Mortality & Sudden Violent Death run by Craig Spence, a leading academic of death in early modern London.

Books:

N. G. Brett-James, ‘The London Bills of Mortality in the 17th century’ Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, 2:6. (2021), 284-309.

A. Hinde, England’s Population: A History Since the Domesday Survey (2003)

J. C. Robertson, ‘Reckoning with London: interpreting the Bills of Mortality before John Graunt’ Urban History, 23:3. (1996), 325-350.

[1] J. Bell, London’s Remembrancer (1665). Unnumbered page.

[2] N. Boyce, ‘Bills of Mortality: tracking disease in early modern London’, The Lancet, 395. (April 2020), 1186.

[3] J. Boulton and L. Schwarz, ‘Yet another inquiry into the trustworthiness of eighteenth-century London’s Bills of Mortality’, Local Population Studies, 85. (2010), 39.

[4] V. Harding, ‘The Population of Early Modern London: A Review of the Published Evidence’ London Journal, 15:2. (1990), 111-128.

[5] Boyce, ‘Bills of Mortality’, 1187.