Names can tell us a lot about the history of a place. Whether this is the name of a town or village, constituent parts of them, such as a particular street, or regional names. It is always interesting, and often useful, for the historian to see what place names might tell us. They can reveal information about stages of settlement, former landowners, historic geographical features, and economies, to name just a few aspects.

In Britain our place names originate from a variety of sources due to the long occupation of much of our land and successive waves of peoples settling. Therefore, before even getting into the meaning of a name, the language used is a helpful indicator. If the name is Norse for example, then it is likely that the place was settled when these people arrived in the area. The researcher must be wary of too much certainty, however. It is always probable that a later wave of migration replaced an earlier settlement. A name change might only follow a shift in a small number of elites while an older culture persisted. In most towns and villages there are millennia of different names showing use and reuse.

Within our places different areas have distinctive names which can be used to build a picture of historic settlement and use. Many researchers focus on these smaller areas as local history studies in themselves. The name of a street, for example, may tell us a great deal about when it was built. Streets were often named after trades which operated there, Tanner Row or Coppergate for example, or after recent or contemporary events and politicians, such as Waterloo Road or Gladstone Street. Streets can also be named after historic features or landowners, such as Bridge Street or Bedford Square.

Derek Harper, Signpost near Two Bridges, Somerset (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Place names are potentially valuable sources of information for the historian but cannot be taken at face value. It is usually necessary to unpick the elements within a place name, breaking it down into its composite parts. Research beyond names themselves to see what they actually mean. There can often be confusion and even dispute in some instances. The mutation of names over time is something to be alert to. The historian must also check the historic evidence as new settlements may have been given a historic-sounding name at a later date. Sometimes new settlements reconstructions can retain old names and other times destroy them. In some cases, those which seem the simplest can in fact be the most historic. There are, for example, many places called ‘Newlands’ which very often originate to when this land was newly cultivated and settled by expanding medieval populations.

Language is of course very prone to regional variation, which must be kept in mind for place names. This is in addition to the linguistic differences which have historically existed across Britain, from Pictish to Cornish and everything in between. Names may mean slightly different things and the same thing may have different words, even within relatively short distances. The importance here is on local (and regional) knowledge.

Information on place names is all around us. To find out about place names some internet searching can be a valuable starting point, to see at least what the commonly held belief is, if not to receive a definitive answer. There may be explanations in local and regional history books where names are mentioned. Older antiquarian works often contain information on older interpretations of names as there has historically been great interest in them. These must be taken with caution as our modern understanding of historical language has improved. But they can be a useful starting point and are very often correct.

It is important to think beyond the names of built-up places when researching. For example, water often retains some of the oldest names and can indicate an ancient past. The names Esk, Eden and Avon are common in Britain and can be traced back to Celtic words for water or river. The study of fieldnames is an entire form of study in itself. These can change over time but can be centuries old and reveal their past use.

Place name studies are an old form of historical research in Britain and this fascinating topic has attracted considerable attention to help us on our way. Comprehensive attempts to record and understand places exist at regional and national level.

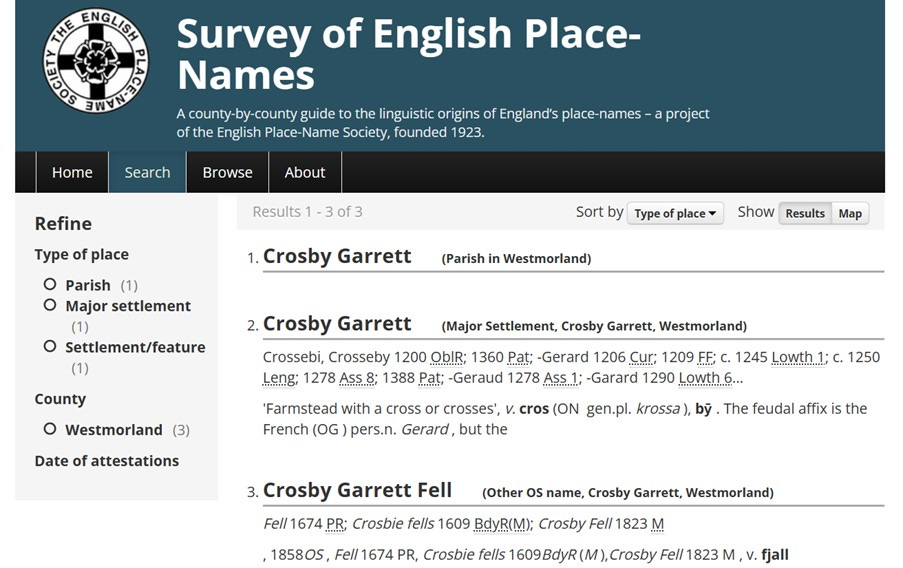

The Survey of English Place-Names, a British Academy Research Project, is one of the longest-running projects of its kind. Since the 1920s, English Place-Name Society scholars have been working on a county-by-county survey of England's place-names, collecting the early forms of names from classical, medieval, and later documents and offering interpretations of their linguistic origins. The Digital Survey makes the place-name scholarship of the last century easy to search, browse, and map.

Search for ‘Crosby Garrett’ on the Survey of English Place-Names website.

Looking for particular places, elements, and historical forms you can use the search engine to find the details across volumes. The results can be further refined by date, type of place, and county. Results for parishes show links to entries places within that parish, such as field names.

The Scottish local historian is directed to the website,

Scottish Place-Name Society – Comann Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba, which provides a wealth of resources on their website.

Welsh researchers are well-served by the Historic Place Names of Wales site, an innovative resource that contains hundreds of thousands of place names collected from historical maps and other sources. It provides a fascinating insight into the land-use, archaeology and history of Wales.

References and Resources:

Paul Cavill, A New Dictionary of English Field Names. (2018)

A.D. Mills, A Dictionary of British Place Names (2011)

John Abernethy, Collins Scottish Place Names (2009)

Dewi Davies, Welsh Place Names and Their Meanings (2016)

John Field, A History of English Field-Names (2014)