For if a person fatigued with long and hard labour, or with a violent agitation of the mind, takes a good dish of chocolate, he shall perceive almost instantly that his faintness shall cease and his strength shall be recovered.[1]

Chocolate is a wonderous sweet treat. One of those rare foods that appears around the world in many cultures. It is often used in celebrations, for example at Easter which is this weekend in the Christian calendar.

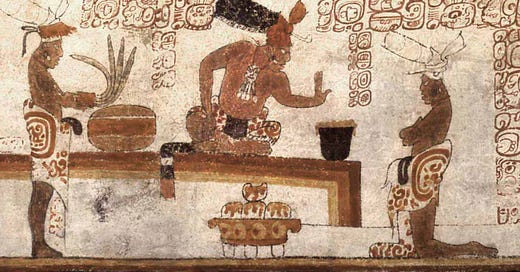

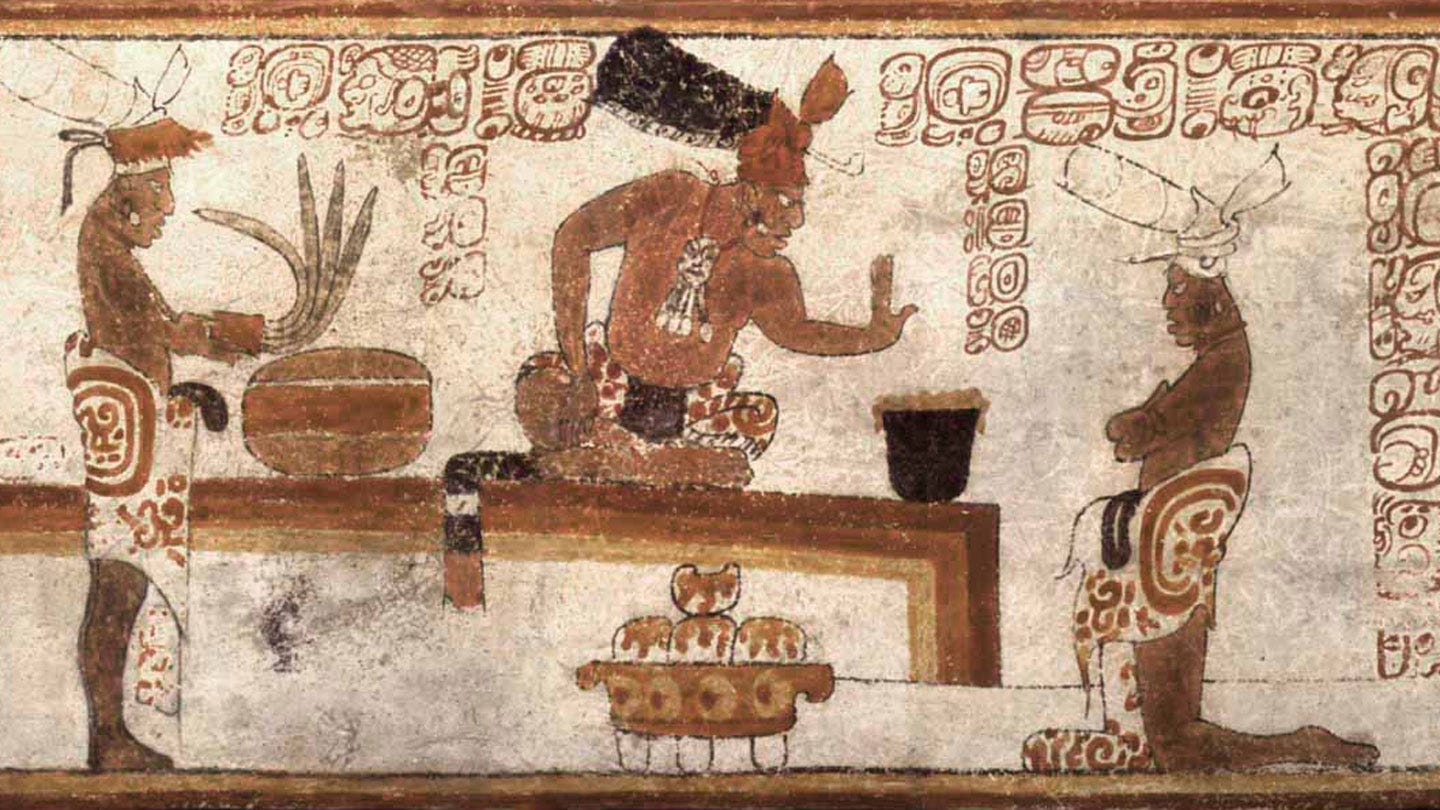

Chocolate is made from cacao seeds which were thought to be the gift of Quetzalcoatl, a creator deity and God of wisdom in ancient Aztec cultures, and were used by the Aztec and Mayan peoples of Mesoamerica. They were very valuable and used as a form of currency, and for rituals around birth, coming of age, marriage, and death, as well as a tribute to rulers. Cacao has a long history, with cultivation dating back to almost 4,000 years ago. It was long thought to have been consumed only as a drink, but recent archaeological research has shown that it was also added to foodstuffs.[2] Once Europeans acquired it, they first used cacao only in its drink form and as a medicine, as it was very bitter.

Painting on the side of a Maya vase depicts a ruler speaking to a kneeling attendant while tamales are prepared. The dark brown bowl might contain cacao. MAYAVASE.COM. Public Domain.

It was only when Europeans started sweetening this bitter drink with honey (as had also been done in Mesoamerica) and eventually with sugar that it grew in popularity, especially in the Spanish court and among aristocratic households. However, there was a darker side to its popularity. Colonial plantations were established to meet the growing European demand for cocoa, were worked by slaves. The legacies of enslavement are still being felt today while leading suppliers of cocoa still have a dark side. A large proportion is now farmed in West African countries with child slavery and trafficking major concerns around the industry.[3] By the twenty-first century initiatives have been introduced to address concerns about cocoa labourers. Fairtrade chocolate targets these issues. While we enjoy our chocolate, the darker side of its popularity past and present should be acknowledged.

Towards the end of the seventeenth century and into the eighteenth the drinking of hot chocolate became entwined with the coffee houses of London and other major cities. England had lagged behind Spain, France and Italy in adopting this new drink, but chocolate soon found popularity. Figures familiar with the London coffee house scene such as the diarist Samuel Pepys attest to its growing popularity. He wrote in his famous diary on 24 November 1664, ‘About noon out with Commissioner Pett, and he and I into a coffee house to drink Jocolatte (sic), very good!’[4] As the chocolate economy boomed, trade cards became common (there is a large collection in the British Museum). The card below announces that Samuel Bennette bought some coffee of Richard Harris, the Chocolate Maker at Tom’s Coffee House in Russell Street, Covent Garden,

Who sells Superfine Vanelloe & Plain Carracca Chocolate. Finest Teas of all sorts, Best High Roasted Turkey Coffee. Spanish Havannah &c. snuffs, Wholesale and Retail at Reasonable Rates.

Draft Bill-head of Richard Haines, chocolate and cocoa dealer (1765). [Heal, 38. 4] © Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

Recipes for drinking chocolate began appearing with frequency in eighteenth-century recipe books.[5] Gradually, chocolate began to be used in food such as biscuits. It appeared in Hans Sloane’s recipe books and it is Sloane who is (disputedly) credited with first combining milk with chocolate. You can view his recipe and a demonstration video here.

Chocolate would have to wait until the nineteenth century to take the popular form it is consumed in today, the chocolate bar. It was in 1828 that Dutch chemist Coenraad Johannes van Houten developed a way to treat cocoa with alkaline salts to remove the bitterness. His father, Casparus, had created a press that removed the fat from roasted cocoa beans, creating a cake, making it easier to create a powder which his son then experimented on. These inventions allowed mass production of chocolate.[6]

Tetiana Bykovets, Chocolate. Unsplash

Later in the century Fry & Son of Bristol developed a mix that produced a smooth paste that could be poured into a mould. They became the largest chocolate manufacturers in the world. Fry & Son, Cadbury’s, and Rowntree’s (all founded by Quakers) became the three big British confectionery companies, holding a near-monopoly on chocolate into the twentieth century. It was Fry’s who produced the first chocolate Easter Egg in 1873.[7]

References and Resources:

R. F. Collins, Chocolate: A Cultural Encyclopedia (2022)

Tasha Marks, ‘The 18th-century chocolate champions’, The British Museum (2018)

Sam Bilton, The History of Chocolate | English Heritage

Why do we eat eggs at Easter? | English Heritage

C. L. McNeil, Chocolate in Mesoamerica: A Cultural History of Cacao (2009)

Nelson Foster and Linda Cordell, eds. Chiles to Chocolates: Foods the Americas gave the World (1992)

Marcy Norton, Sacred Gifts, Profane Pleasures: A History of Tobacco and Chocolate in the Atlantic World (2008)

Emma Kay, A Dark History of Chocolate (2021)

The Dark Side of Chocolate documentary (2010)

The experienced English house-keeper, consisting of near 800 original receipts by Elizabeth Raffald (1769)

The Cook’s and Confectioner’s Dictionary (1723)

[1] D. de Quélus, The Natural History of Chocolate [Trans. Richard Brookes] (1724), 51.

[2] C. L. McNeil, Chocolate in Mesoamerica: A Cultural History of Cacao (2009)

[3] Oliver Balch, ‘Child labour: the dark truth behind chocolate production’, Raconteur (2018)

[4] Samuel Pepys, Diary, ‘Thursday 24 November 1664’.

[5] Such as The experienced English house-keeper, consisting of near 800 original receipts by Elizabeth Raffald (1769) and The Cook’s and Confectioner’s Dictionary (1723).

[6] R. F. Collins, Chocolate: A Cultural Encyclopedia (2022), 368.