Coroners in England were elected officials and, since the formalisation of the office in 1194, they were typically appointed for life.[1] The coroners’ role was to investigate sudden, suspicious, or violent deaths, habitually within a forty-eight-hour window after the incident. These investigations were conducted in front of a jury of local men near the location of the death, in a local alehouse, or parish workhouse. Because both coroners and the jurors were drawn from their local districts, they were regularly able to provide intimate knowledge about the individual involved in the suspicious death. They would also have been aware of the reputations of witnesses and know the local neighbourhood and topographical details. Jurors would examine the corpse and scene of death, question family, and friends, and listen to local gossip. On occasion, they may even have even re-enacted the death.[2] From their findings, they would produce the coroner inquisitions. These records are a rich source for the historian to examine, but their survival is patchy.

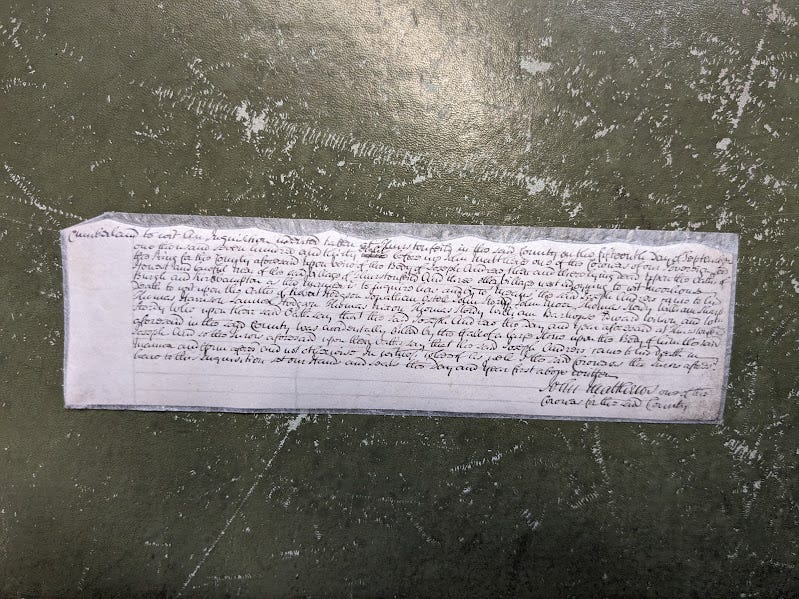

Northern and North Eastern Assizes. Andrew, Joseph - coroner's inquest held in Cumberland 1738. [TNA ASSI 45/21/1E]. Image copyright of The National Archives. Not to be reproduced without permission.

In London for the early modern period, except for one coroner’s roll from 1590, the coroners’ inquests after this date into the eighteenth century were never returned to the central courts and are missing.[3] The Middlesex coroners’ inquests reappeared in 1747, the Westminster coroners’ inquests reappeared in 1760, and the inquests from the City of London only reappeared in 1786, limiting the ability to trace verdicts relating to posthumous trials upon the corpse of a suspicious death. The summarised findings of the inquisitions are intermittently referenced in other sources, and by the eighteenth century were occasionally reported in newspapers.

It is possible to sporadically come across some of the depositions taken before the coroners in London which have survived in various collections of session papers, such as one from the ‘May Sessions’ of 1676 concerning a woman named Sarah George. The informant was a Rachel Cooper, spinster, who reported that on the evening of Thursday 20 April, she had gone to visit Mr and Mrs George. When she arrived, Mr George went upstairs to call his wife then ‘ran down stairs presently crying out his wife had murdered her self’. Rachel Cooper went upstairs and ‘sawe Sarah George in her bed bleeding but alive’; later that evening she died. In the deposition Ms Cooper goes on to say that Sarah George ‘did frequently talke of leaving her husband sayeing shee would not live w[i]th him any longer’. Apparently, Sarah George often beat and would bite her husband too, putting him in fear for his own life. In the bedroom, there was ‘a bloody Rasier lyeing in a Chaire and that from the Chaire upon the floore to the bed there were dropps of blood’.[4] Sarah George had cut her throat. The coroner clearly investigated her death but the verdict from the inquisition is lost, along with any other sources that reference this death.

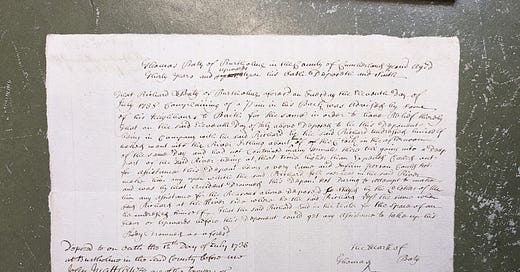

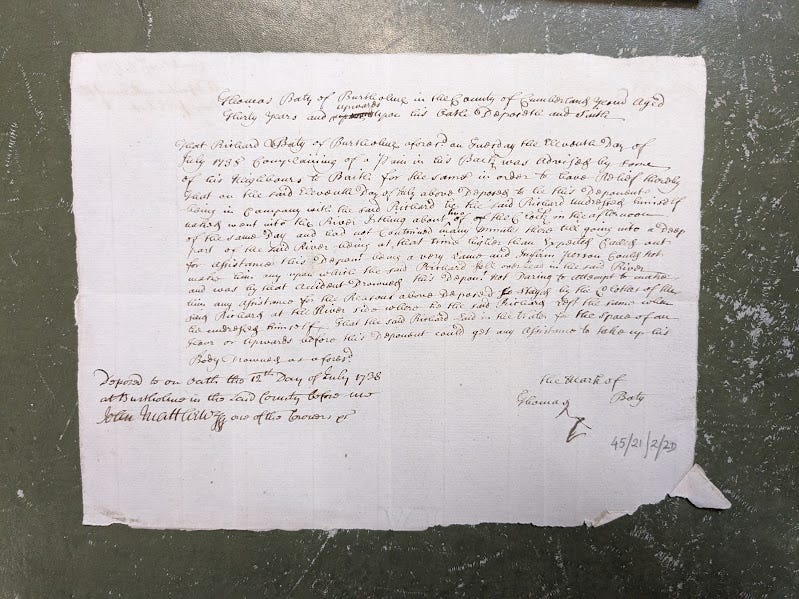

Northern and North Eastern Assize Circuit. Baty, Richard - deposition taken in Cumberland concerning accidental drowning 1738. [TNA ASSI 45/21/2D] Image copyright of The National Archives. Not to be reproduced without permission.

In parish registers a clerk may have helpfully written ‘coroners quest’ beside some entries but unless the actual record of the posthumous trial is uncovered many significant details of a case will be missing. Outside London, the survival of coroners’ inquests is again patchy but not absent and those that survive can be examined at The National Archives. A useful guide to these is accessible here. The London inquests that do survive can be explored through the London Lives website here. Therefore, if you come across an individual who died a sudden or suspicious death, or the parish register notes ‘Coroners Quest’ by their name it is worth cross-referencing them with the inquests. You may be lucky enough to have an inquest survive for the case.

References and Resources:

P. Fisher, PhD Thesis, ‘The Politics of Sudden Death: The Office and Role of the Coroner in England and Wales, 1726-1888’ (2007)

J. Gibson and C. Rogers, Coroners’ Records in England and Wales (2000)

C. Loar, ‘Medical Knowledge and the Early Modern English Coroner's Inquest’, Social History of Medicine, Volume 23, Issue 3, 1 December 2010

J. Impey, The Office and Duty of Coroners (1800)

[1] P. Fisher, PhD Thesis, ‘The Politics of Sudden Death: The Office and Role of the Coroner in England and Wales, 1726-1888’ (Leicester University, 2007), pp. 1,3; For a guide to the survival of records see, J. Gibson and C. Rogers, Coroners’ Records in England and Wales (Birmingham: Federation of Family History Societies, 2000 edn.).

[2] C. Loar, ‘Medical Knowledge and the Early Modern English Coroner's Inquest’, Social History of Medicine, Volume 23, Issue 3, 1 December 2010, p. 477.

[3] Coroners’ inquests from 1300 - 1378 and the single one from 1590 are at the London Metropolitan Archives, CLA/04/IQ/01/001-011.

[4] LMA, CLA/047/LJ/13/1676/004.