Diaries and Journals

England (and beyond)

I can never understand how the scribbles of such an ordinary person ... can possibly have value. - Nella Last

Diaries and journals allow the researcher to get at what a person in the past thought and felt, and how they saw and interpreted their world. There are many types of diaries and journals and many ways the historian can use them. Diaries and journals are similar, but it is usually accepted that a journal is the more personal of the two items, written in any type of notebook and kept sporadically. A diary is kept every day and often records daily activities in a formulated notebook. Medical diaries and journals, travel diaries and journals, weather diaries, diaries or journals about the natural world, daily diaries, the occasional journal kept in no fixed format, and the accidental diary or journal, to name but a few, are all windows into the past.

Let us face it, every historian is nosey by nature. Something about reading someone else’s private thoughts, observations, and daily activities partly fulfil our curiosity. They are fascinating, being cumulative rather than summative and with many secrets to reveal. Nella Last, whose quote began this post, may not have understood the allure of reading a diary but ironically hers, written for the Mass-Observation project, has been read by thousands of people around the world. As one of the most common personal objects a historian has access to (along with letters), they are a treasured source.

Old diary clasp. Public Domain.

The word ‘diary’ comes from the Latin diarium (daily allowance) and although diaries have been kept in various forms for a very long time it was in the seventeenth century that they came into their own in England.[1] In 1607 Ben Johnson wrote in his comedy play Volpone ‘This is my Diary, Wherein I note my actions of the day’ so the practice was clearly well enough known by this point. There is a very handy ‘Diaries Timeline’ here.

In 1796 the stationer John Letts set up a business in the Royal Exchange. While providing his service to traders and merchants he noted that they required diaries to track ships, the weather, tides, and their finances. ‘Letts sensed that there could be a market for more general diaries of this type, but ones that were future-dated, so that the diary owner could plan ahead and not simply record the events of the day’. [2] Thus in 1812 Letts produced the first commercial diary. He expanded into publishing a range of different sized and formatted diaries. The endeavour was a success. Our modern idea of a diary was born from Letts’s creations.

Often written for and about oneself, although some were designed to be read by others, the researcher is often confronted with the most difficult of penmanship and, such as in the case of the famous diaries of Samuel Pepys or Anne Lister, code and shorthand. An example of the original pages of Pepys diary can be seen here.

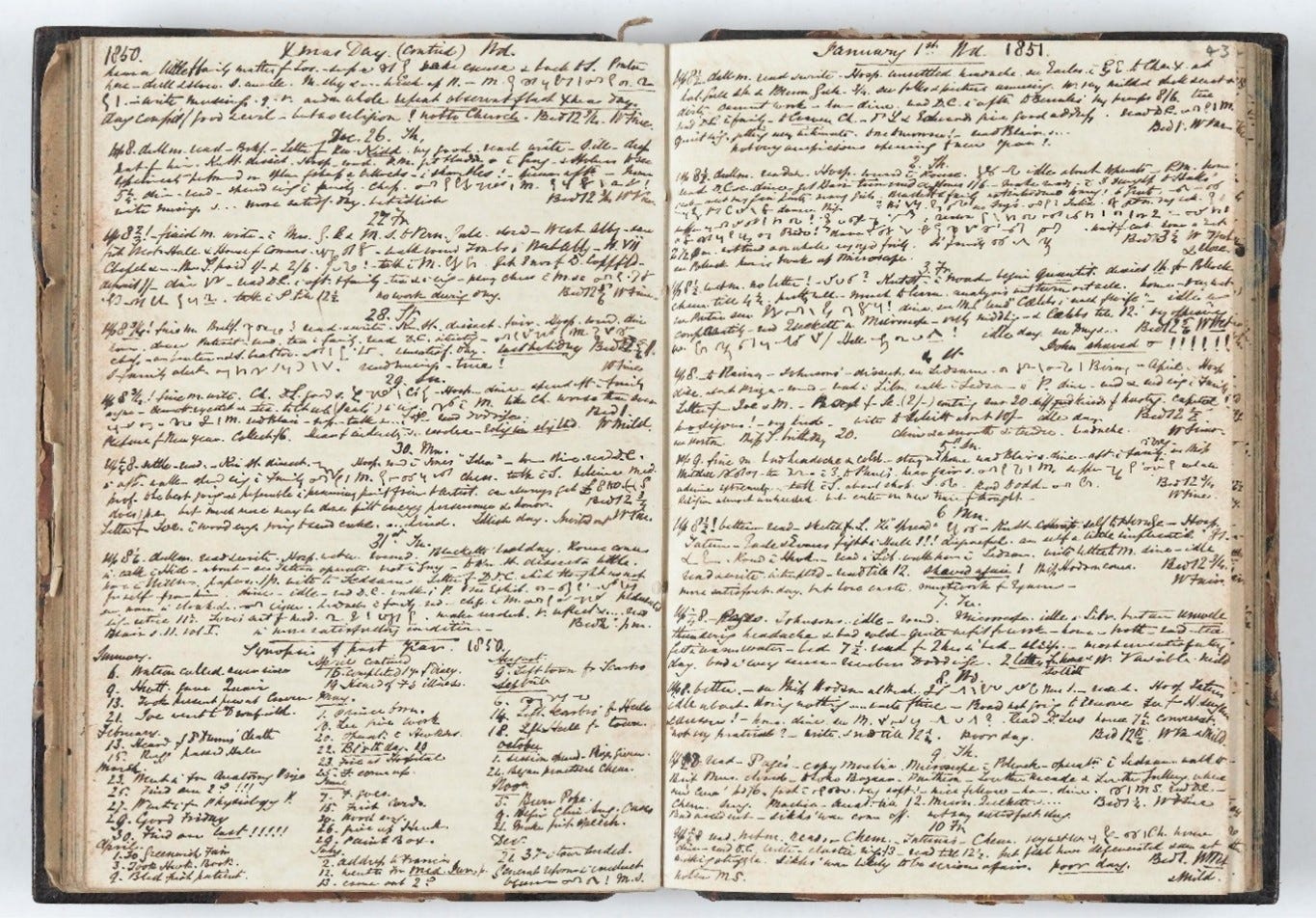

Page from Henry Vandyke Carter's Journal for 25th December 1850-7th Jan 1851. Wellcome Collection. (CC BY 4.0)

Diaries are material objects, how they were put together and what they are made of also have stories to tell. The life of the object, how and why it survived, was conserved and preserved to the point that modern historians are reading it must all be considered. Lastly and crucially, care must always be taken when using diaries to ask the age-old questions of who wrote it, for who, when, and why. As Virginia Woolf asks in her own diary, ‘Whom do I tell when I tell the blank page?’

Further References and Resources

Below are some famous/interesting diaries and journals along with the years they cover, and links to the text or further information:

The Diary of Samuel Pepys (1660-1669)

The Diary of John Evelyn (1620-1706)

The Diary Lady Sarah Cowper (1700-1716)

The Diary of Thomas Turner (1754-1765)

The Diaries of Sarah Hurst (1759-1762)

The Diary of Frances Burney (1768-1778; and other bits for later dates)

James Boswell’s Diaries (1762-3, London Journal. Many other journals of his travels until 1795)

Dorothy Wordsworth Journals (1800-1803, and other bits)

Anne Lister Diaries (1806-1840)

Diary, Reminiscences, and Correspondence of Henry Crabb Robinson (1775-1867)

The Diaries of Hannah Cullwick, Victorian Maidservant (1854-1873)

Queen Victoria’s Journals (1832-1901)

Edith Holden’s naturalist diary of 1906 (1906)

The Diaries of Beatrice Webb (1912-1924)

The Diaries of Nella Last (1939-1966)

A Writers Diary: Virginia Woolf (1918-1941)

The Benn Diaries (1940-1990)

Books:

L. Sangha and J. Willis, (ed.), Understanding Early Modern Primary Sources (2016)

A. Johnson, A Brief History of Diaries: From Pepys to Blogs (2011)

[1] According to the Oxford English Dictionary, https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/52076?result=1&rskey=fuqkUN& [Accessed 19 September 2022].

[2] A. Room, ‘Letts, John (bap. 1772, d. 1851), stationer and diary publisher’. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-39023 [Accessed 19 September 2022].

Since learning my 2x great grandmother was a midwife — and that midwives often kept detailed diaries — I’ve been pestering every relative I come across about any written family artifacts they might have. It has definitely become both my obsession and my holy grail.

I’ve read a number of midwife diaries, and just know my ancestor’s would be filled with delicious details and personality. 😉