Ascending a mountain as a leisure activity was an unfathomable concept throughout much of British history. Mountains were set apart from most people, obstructions in contrast to the practical beauty of fertile land. Until 1854 ‘the British hardly concerned themselves with climbing except as a means of exploiting the animal and mineral resources of sea cliffs and mountains, or gaining a military advantage’.[1]

The seventeenth century saw the first recorded ‘summitting’ of a mountain in Britain. Thomas Johnson, the Father of British Field Botany, was a gentleman’s son and apothecary who travelled across England and Wales to collect specimens. In 1639 he ascended Yr Wyddfa (Snowdon). Perhaps he was drawn by the Snowdon Lily which grows on a few cliffs in Snowdonia.

In 1798 the Reverends William Bingley and Peter Williams ascended Clogwyn du'r Arddu, a high cliff on the north flank of Snowdon. They too were in search of botanical specimens, saw the rare Snowdon Lily and, in the process, undertook the first recorded British rock climb. The first documented ascent of Ben Nevis, Britain’s tallest mountain was by James Robertson in 1771, another botanist collecting specimens. His exact reasons for summiting are unknown but he did write that it was believed to be Britain’s highest mountain and perhaps this spurred him to the top.

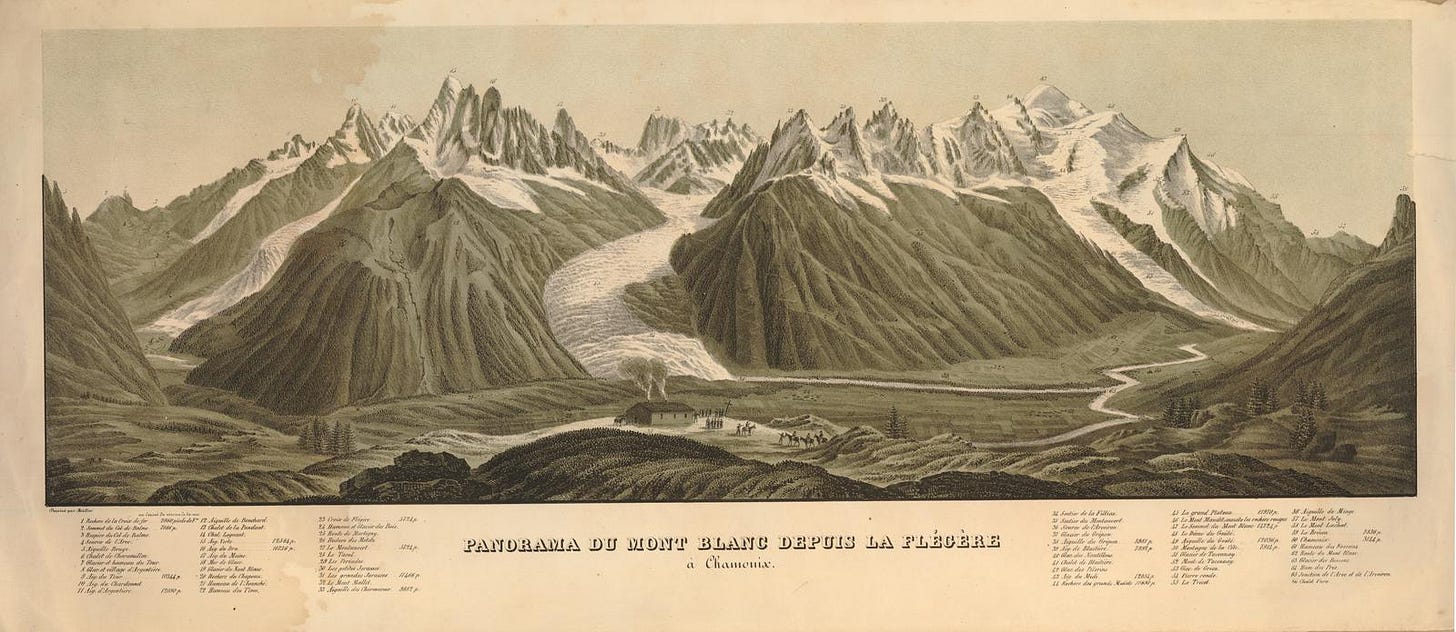

Panorama du mont Blanc depuis la Flégére à Chamonix © Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

In eighteenth century Europe it was increasingly acceptable to climb a mountain for pleasure, even if the practice was considered bizarre by many and only attainable by the upper classes. In 1760 prize money was offered for a successful summitting of Mont Blanc in the Alps, the highest peak in western Europe, though this was not achieved until 1786.

In this era of Enlightenment there was a growing belief that Man ought to connect with the natural world and this was done through writing. Thomas West published A Guide to the Lakes in 1778 encouraging visitors to the English Lake District.[2] Key to the development of British mountaineering were the Romantic poets. John Keats undertook a walking tour of the British Isles in 1818, which included an ascent of Ben Nevis. William and Dorothy Wordsworth were noted for their love of nature and rambling.[3] Samuel Taylor Coleridge undertook the first recorded recreational rock climb. As part of a solitary walking trip around the Lake District he climbed up Scafell, the second highest peak in England. With a storm coming in he picked a path down and came to a ridge today known as Broad Stand. The moment is regarded as foundational to the history of British mountain climbing:

I put my hands on the Ledge, & dropped down / in a few yards came just such another / I dropped that too / and yet another, seemed not higher-I would not stand for a trifle / so I dropped that too / but the stretching of the muscle { [s] } of my hands & arms, & the jolt of the Fall on my Feet, put my whole Limbs in a Tremble…[4]

Peter S., Broad Stand on Scafell (CC BY-SA 2.0)

As the pursuits of rambling, scrambling, and climbing developed across the world during the nineteenth century, Britain and the British were to play a key part. In the early nineteenth century a growing number of people, mostly upper class, saw mountains as opportunites for pleasure. This emerged within a wider European appreciation. The so-called ‘Golden Age of Mountaineering’ in the mid-century saw the conquest of the great peaks of the Alps. Many achievements were by Brits from to Alfred Willis’s team on the Wetterhorn in 1854 to the Matterhorn in 1865 by a party led by Edward Whymper. The sport was fraught with issues though from disputes over whether Willis had indeed been the first to summit and the infamous deaths of four members of Whymper’s party.

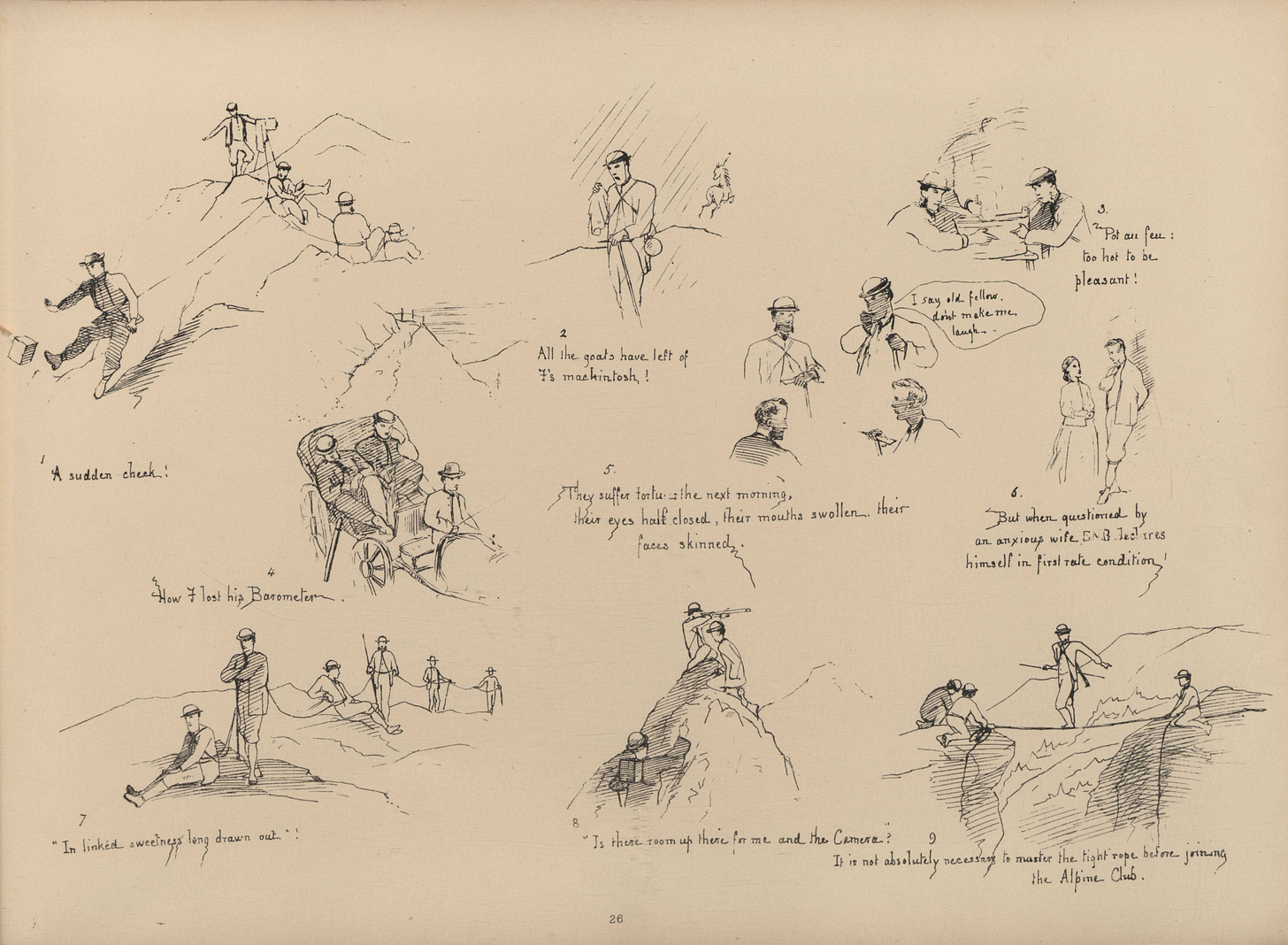

This pastime, known as ‘Alpinism’ was brought back to Britain where the mountains were lesser than the Continent but the quality of the climbing good. In 1857 the Alpine Club was formed. The first mountaineering club in the world it was an exclusive institution for gentleman climbers. The qualifications were vague but with some sense that good experience of mountains over a certain height was required, a barrier which meant experience outside Britain. No women were permitted either. The Ladies Alpine Club was formed in 1907 but there were many women in the early movement. Elizabeth Tuckett made a series of sketches of an Alpine Club trip, first published in 1864.

Elizabeth Tuckett, How we spent the summer, or, A Voyage en zigzag in Switzerland and Tyrol with some members of the Alpine Club (1864), 58. Public Domain.

The Club promoted an elite and international view of the sport with their journal containing accounts of ascents across the world. There were also reviews of equipment and advice on best practice. Mountaineering rules, techniques and terms were established by the Club who also led fundamental changes in equipment such as testing the best lightweight but strong rope.

An important legacy of the early development of British mountaineering is the widespread appreciation of these landscapes in the lives of subsequent generations, down to our own.

References and Resources:

Simon Thompson, Unjustifiable Risk?: The Story of British Climbing (2012)

Simon Bainbridge, ‘Writing from ‘the perilous ridge’: Romanticism and the Invention of Rock Climbing’, Romanticism 19:3 (2013), 246-260.

Coleridge's account of his descent of Broad Stand.

Elizabeth Tuckett, How we spent the summer, or, A Voyage en zigzag in Switzerland and Tyrol with some members of the Alpine Club (1864)

[1] Simon Thompson, Unjustifiable Risk?: The Story of British Climbing (2012), 7.

[2] Thomas West, A guide to the lakes, in Cumberland, Westmorland, and Lancashire (1780)

[3] Simon Bainbridge, ‘Writing from ‘the perilous ridge’: Romanticism and the Invention of Rock Climbing’, Romanticism 19:3 (2013), 246-260.

[4] Coleridge's account described in a letter to Sara Hutchinson.