‘It must, however, be confessed, that these things have their use; and are, besides, vehicles of much amusement.’ – George Crabbe, ‘To the Reader’, The Newspaper (1785), 125.

In the seventeenth century, newspapers burst into English daily life in a different way than earlier newssheets and pamphlets. Regular publications covered news and gossip from across England and far further afield. Early periodicals existed alongside pamphlets, ballads, and posters but began to carve out a place for themselves lasting until the present day, providing historians with a wealth of information.

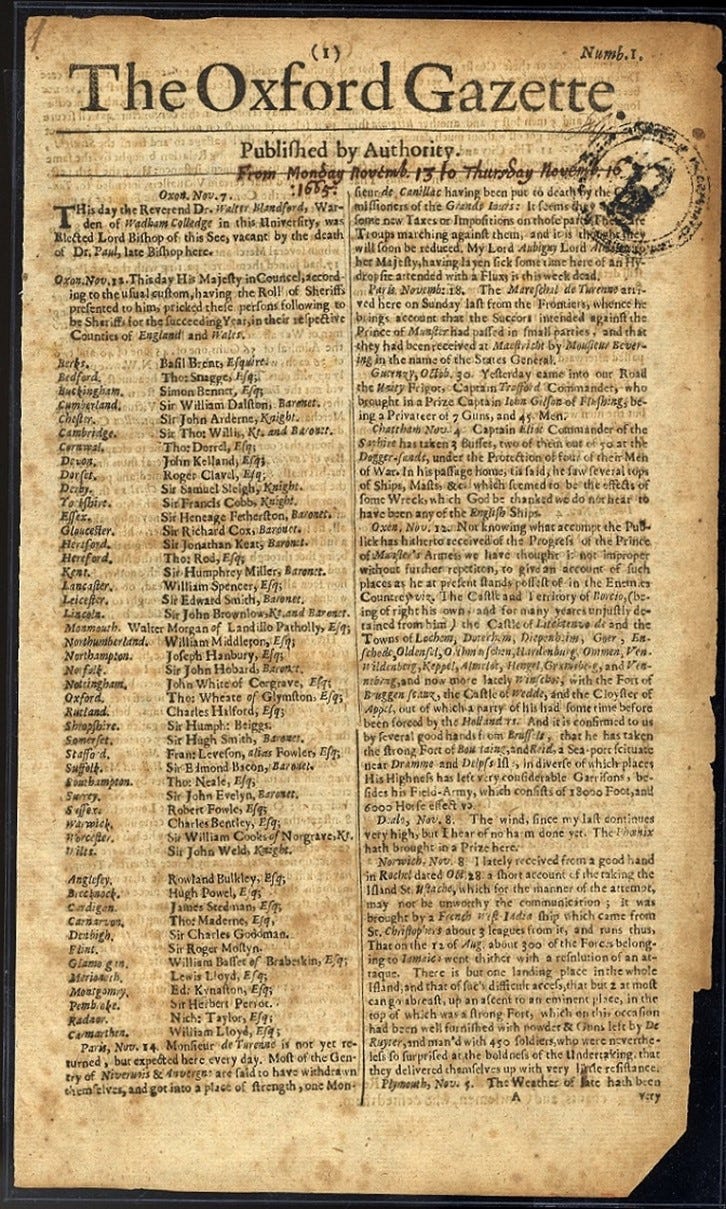

The Civil Wars escalated the demand for news and by the Restoration, many news sheets were circulating. In 1665 the Oxford Gazette arrived; known as the London Gazette once the court returned to London after the plague. It was the first ‘journal of record and the newspaper of the Crown’ under the Licensing Act of 1662.[1] It is still published to this day and its catalogue can be searched here. This Act lapsed between 1679 to 1685 and again in 1692 creating a proliferation of unlicensed newspapers. In 1695 the Commons refused to renew it. The publications that arrived after this included the Historical Account, the Flying Post, the Post Boy, and the Post Man. By 1704 an estimate of 44,000 newspapers were published weekly.[2]

The Oxford Gazette. Oxford, England (reprinted in London) November 13-16, 1665 (No. 1) Public Domain.

The first regular English daily newspaper appeared in 1702 in the form of the Daily Courant and by 1712 twenty single-leaf papers were being regularly published in London each week.[3] Recurrent attempts to enact legislation failed, but in 1712 a system of taxation curbed production slightly. Several newspapers collapsed, but there was a loophole in the Act, for they had not defined what a newspaper was, and some began to register as pamphlets which had a much lower duty. Provincial papers also became more frequent initially taking most of their news from London publications but slowly finding their own voice.

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, newspapers were everywhere. Several are still recognisable today such as The Times which began publication in 1785 and The Observer which began Sunday publications in 1791. By 1801 16 million copies of newspapers were in circulation annually.

Early English Newspapers. The Spectator, The Tatler, The Free Briton, and The London Gazette that came up for auction at Dominic Winters Auctioneers in 2020. Public Domain.

The researcher should be aware of a few things when using newspapers. Forgeries are out there. In the 1740s, three issues of a periodical newspaper dated 1588 were printed, it was entitled The English Mercurie. Some were bequeathed to the British Museum and not discovered as fakes until 1839.[4] Be aware of newspapers such as The Popish Courant which printed many fake prophecies, mock advertisements, and fictional stories and was not alone in doing so, and of course bear in mind the aim of the different publications.

Care, of course, must be taken when using them, but newspapers provide a wealth of information beyond what may initially appear. They allow insights into what people thought was happening, and readers believed this, and so they give valuable insights into the past. Newspapers demonstrate social change, long-term trends, and contain wonderful details about people, places, and things.

Early newspapers are held a range of local and national institutions. The best place to find newspapers online is The British Newspaper Archives, which is also available through a FindMyPast subscription. If you have access to Gale Historic Newspapers, the collection includes the Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Burney Newspaper Collection which contains more than 1,000 early pamphlets, proclamations, newsbooks and newspapers. The Times Digital Archive covers the period 1785-1985. When keyword searching digitised newspapers be aware that OCR technology has been used and so letters and words may be misrepresented.

In the late eighteenth century Jean Louis de Lolme noted of newspapers that ‘every man, down to the labourer, peruses them with a sort of eagerness’, the historian should do likewise.[5]

Refences and Resources:

There are many sources with which to learn more, in addition to the specific resources mentioned throughout this post. Moira Goff’s guide to Early History of the English Newspaper is a good starting point, it can be accessed here.

‘Newspaper Archives’, Historic UK History Magazine

H. Barker, Newspapers, Politics and English Society, 1695-1855 (2000)

J. Black, The English Press in the Eighteenth Century (1987)

B. Clarke, From Grub Street to Fleet Street: An Illustrated History of English Newspapers to 1899 (2004)

M. Harris, London Newspapers in the Age of Walpole: A Study in the Origins of the Modern English Press (1987)

J. Raymond (ed.), News, Newspapers, and Society in Early Modern Britain (1999)

[1] https://www.thegazette.co.uk/history

[2] J. Black, The English Press in the Eighteenth Century (1987), 8.

[3] M. Harris, London Newspapers in the Age of Walpole: A Study of the Origins of the Modern English Press (1987), 19.

[4] J. Raymond, ‘Introduction: Newspapers, Forgeries, Histories’ in J. Raymond (ed.), News, Newspapers, and Society in Early Modern Britain (1999), 1-11.

[5] J. L. de Lolme, The Constitution of England, or an Account of the English Government (London, 1784), 300.