In the early modern period, the medical marketplace had a tripartite division of physicians, surgeons, and then apothecaries. The tripartite system was one that was strict in areas of continental Europe but much less so in England where medical practice was neither well-organised nor firmly controlled.[1] Alongside these official medical avenues were the ‘irregulars’ who people would have encountered more frequently.

A young male physician holding the hand of a female patient. Mezzotint 1788. Wellcome Collection (Public Domain)

The top medical professionals were the physicians. The College of Physicians was chartered in 1518, although they were not ‘Royal’ until the late seventeenth century. They regulated other practitioners, restricted membership, and often drew the attention of reformers such as William Dell who maintained that healing had been perverted by the corrupt, privileged clique who controlled the college. They also blocked the Swiss reformer Paracelsus and his newer approach to healing and even opposed such things as replacing Latin with English in medical textbooks.[2] The only way into the College of Physicians was through Oxbridge, although the quality of the education received garnered a reputation for being quite poor. Graduates were widely read in classical literature and learned in some modern information however, unlike the universities abroad they were not very hands-on.[3] In fact other than to take a pulse they rarely touched their patients.[4] The role of the physician was to diagnose the complaint, make a prognosis of likely developments, prescribe the treatment and medicines and provide advice. Any medicine that was prescribed would then be dispensed by an apothecary.

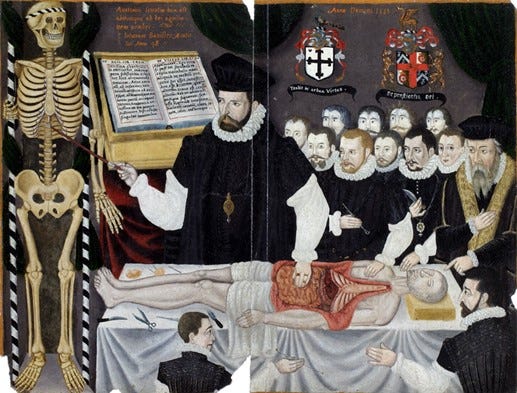

Master John Banister's Anatomical Tables, with Figures. Barber-Surgeons' Hall, Monkwell Street, London c. 1580. University of Glasgow (Public Domain)

Surgeons, dealt with external medicine, dressings, dislocations, setting broken bones and amputating limbs, pulling teeth, and letting blood. Theirs was a manual craft rather than an intellectual science, work that was with the ‘hand not the head’.[5] There were also a few female surgeons, although very rare but never a female physician.[6] Surgeons and barbers were lumped together. The Barber Surgeons Company of London dates from 1540 and it was not until 1745 that the two disciplines separated.[7] Outside London, Barber-Surgeon’s companies were established in twenty-six English urban centres.[8] To become a surgeon an apprenticeship of at least seven years was required.

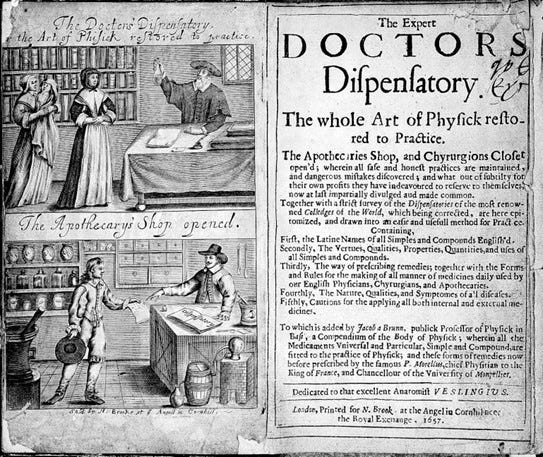

The lowest members of the tripartite division were the apothecaries. They kept a shop, and pursued a trade, and dispensed prescriptions. To become an apothecary a seven-year apprenticeship was the norm. Until 1617 they were joined to the Grocers Company.[9] Apothecaries often sought to prescribe on their own authority, and this caused friction with the physicians. From 1704 apothecaries had the right to practice medicine though not to be paid for it.[10] They were of course paid, but at a much lower rate.[11]

Frontispiece to Pierre Morel, The expert doctors dispensatory…(1657). Wellcome Collection (Public Domain)

Most of the urban population had access to an integrated pyramid of practitioners in the medical marketplace beyond the tripartite division. Patients were critical, sceptical, and well informed.[12] Diaries and letters show people self-diagnosing rather than paying for a medical practitioner or shopping around for various remedies.[13] For example, Grocers and peddlers sold drugs, blacksmiths and farriers drew teeth and set bones, and many itinerants hawked wonder cures. Towns and villages and even big cities had wise or cunning men and women well versed in herb lore (some also dealing in magical remedies). There were also neighbours, friends and relatives who all provided some type of diagnosis when a person became ill.[14] The so-called ‘quacks’ were very good at adapting and adopting fads quickly and employed the technologies of commercialisation, notably the press, to advertise the power of their remedies.[15]

The Miserable Mountebank. Early Broadside and Ballads Archive, EBBA 33197. The National Library of Scotland. (CC BY-NC 4.0)

It is impossible to know how many medical practitioners existed in early modern England. The first national medical registers were not published until around 1780, listing about 3000 but the total must have been much higher.[16] It was with the foundation of the big hospitals; St Thomas’, St Bartholomew’s, Westminster, Guy’s, St Georges’, London, and Middlesex between 1720 and 1750 that the medical marketplace dramatically altered. By 1800 all sizable towns had a hospital and more specialised ones were created, such as St Luke’s and the Foundling Hospital. The hospital movement benefited the medical profession and encouraged teaching within them.[17] A new medical man, first called the surgeon-apothecary, the general practitioner, emerged.[18]

References and Resources:

M. Pelling, The Common Lot: Sickness, Medical Occupations and the Urban Poor in Early Modern England (1998)

R. Porter, Disease, Medicine and Society in England 1550-1860 (1993)

C. Lawrence, Medicine in the Making of Modern Britain 1700-1920 (1994)

W. F. Bynum, Science and the Practice of Medicine in the Nineteenth Century (1994)

M. S. R. Jenner and P. Wallis (eds), Medicine and the Market in England and Its Colonies, c.1450-c.1850 (2007)

Early Modern Practitioners Project

Royal College of Physicians: Historical research materials

[1] M. Pelling, The Common Lot: Sickness, Medical Occupations and the Urban Poor in Early Modern England (1998), 244.

[2] R. Porter, Disease, Medicine and Society in England 1550-1860 (1993), 13.

[3] Ibid., 14.

[4] C. Lawrence, Medicine in the Making of Modern Britain 1700-1920 (1994), 10.

[5] Porter, Disease, Medicine and Society, 16-18.

[6] W. F. Bynum, Science and the Practice of Medicine in the Nineteenth Century (1994), 3.

[7] Porter, Disease, Medicine and Society, 18; C. Lawrence, Medicine in the Making of Modern Britain 1700-1920 (1994), 12.

[8] Pelling, The Common Lot, 209.

[9] Ibid., 33.

[10] Porter, Disease, Medicine and Society, 34.

[11] Lawrence, Medicine in the Making of Modern Britain, 13.

[12] Pelling, The Common Lot, 241.

[13] Porter, Disease, Medicine and Society, 29-31.

[14] Lawrence, Medicine in the Making of Modern Britain, 8.

[15] Ibid., 15.

[16] Porter, Disease, Medicine and Society, 19.

[17] Ibid., 35-38.

[18] Lawrence, Medicine in the Making of Modern Britain, 14.