Early Quakers

England

On 13 January 1691, shortly before ten o’clock in the evening, George Fox, the founder of Quakerism, died of congestive heart failure. Two days earlier he had preached at the Gracechurch Street Meeting in London, where he mentioned to some of those present that he felt a coldness near his heart. Fox retired to the nearby house of another Quaker, Henry Gouldney, and to reassure those who came to his bedside he said: 'All is well. The Seed of God reigns over all, and over Death it self'.[1] It was here in Gouldney’s house that he died.

George Fox was a shoemaker’s apprentice from Leicestershire who, in 1647, at the age of twenty-three, found enlightenment. In 1652, after travelling across the northern counties of England and experiencing transforming visions, Fox had a series of religious experiences at Pendle Hill, Firbank Fell, and Swarthmoor Hall which marked the beginning of the Quaker movement. He was not alone as a founder of what was to become Quakerism, others such as James Nayler, Richard Farnworth, William Dewsbury, Richard Hubberthorne, and Edward Burrough were equally important to the early formation, but Fox largely dominates the existing view of early Quakerism through the journal he left behind.[2]

Portrait of George Fox attributed to Peter Lely - Swarthmore College ©Public Domain.

The Quaker movement, with speed, travelled south to London. In the bustling metropolis of 1654, a woman named Isabel Buttery and her female companion arrived from the north and began distributing a paper written by George Fox. For their troubles, the two women were arrested for Sabbath breaking and put into Bridewell, an incident that would become a common occurrence among the early Quakers who were often subjected to violent attacks and imprisonment. The Quaker message had however caught hold and gained a firm footing within the metropolis.[3] It would continue to spread beyond England, to Ireland, Europe, and the Americas.

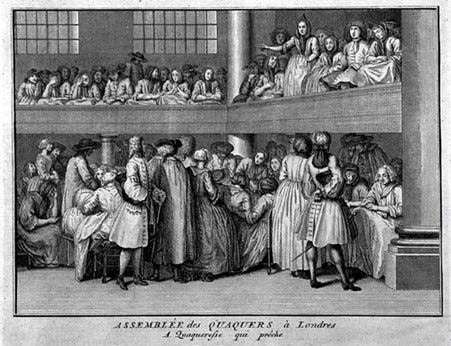

A female Quaker preaches at a meeting in London in the 18th century. ©Public Domain.

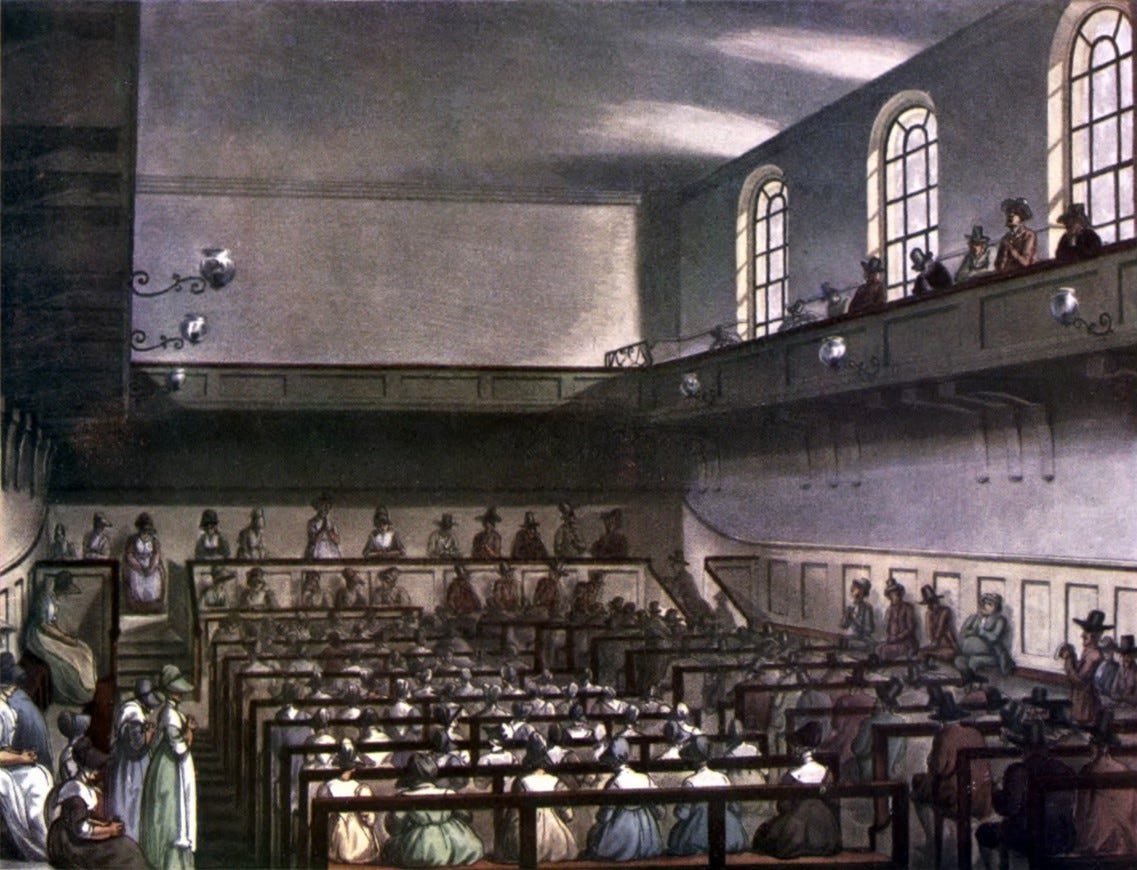

Quakers’ beliefs emphasised a participatory practice, both in how followers should interact with each other and with the world at large. Central to Quaker belief was the idea of the light of Christ’s existence within everyone, and it was awakening this light that was at the forefront of Quaker campaigns. Quakers abandoned the formalised structures of other religions and honorific titles, believing everyone was spiritually equal. To this end, they refused to doff hats, swear oaths, or pay tithes, and justified the inclusion of women participating and even preaching within their religion.[4]

Conservative Friends worshipping in London in 1809. Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827) and Augustus Charles Pugin (1762–1832) ©Public Domain.

The Quakers’ own narrative, output of printed material and detailed record keeping make them accessible to historians. Quaker print forged a recognisable Quaker identity and began a national campaign.[5] The Quaker population of England was never large. Between 1663 and 1700, when the average population of the country was over five million, there were only 40,000 members of the Society of Friends.[6] By 1750, when the general population had nearly doubled, the number of Quakers had declined to 30,000, roughly 0.3 percent.[7] However, unlike some of the other movements that sprang up at the same time, Quakerism has endured into the twenty-first century, adapting and transforming when necessary, but still retaining many of the core principles and practices from their foundation. The carefully maintained and treasured records of their own history played a part in this.

Further References and Resources:

Friends House in London houses The Library of the Society of Friends and its archives. There are two journals dedicated to the study of Quakerism; Quaker History and Quaker Studies (Quaker Studies Research Association). The Quaker Family History Society is helpful for those tracing Quaker ancestors. Quakers set out what it meant to follow their teaching in The Book of Discipline now known as Quaker Faith and Practice and accessible online here. It is the best starting point to understand the movement and includes much from Fox’s journal.

P. Dandelion, The Quakers: A Very Short Introduction (2008).

S. W. Angell and P. Dandelion (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Quaker Studies (2013).

R. Moor, The Light in Their Consciences: The Early Quakers in Britain, 1646-1666 (2000).

[1] H. Larry Ingle, ‘Fox, George (1624–1691), a founder of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers)’. ODNB. September 23, 2004. https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-10031 [accessed, 8 Jan. 2020].

[2] B. Reay, The Quakers and the English Revolution (1985), 8; R. Moor, The Light in Their Consciences: The Early Quakers in Britain, 1646-1666 (2000), 7-8, 15.

[3] W. Beck and T. Frederick Ball, The London Friends’ Meetings (1869), 19-20.

[4] K. Peters, Print Culture and the Early Quakers (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 2; the inclusion of women has attracted a substantial amount of scholarship, for example see: C. Gill, Women in the Seventeenth-Century Quaker Community: A Literary Study of Political Identities, 1650-1700 (2005); P. Mack, Visionary Women: Ecstatic Prophecy in Seventeenth-Century England (1994); S. Stanley Holton, Quaker Women: Personal Life, Memory and Radicalism in the Lives of Women Friends, 1780-1930 (2007).

[5] Peters, Print Culture, 10-11.

[6] P. C. O’Donnell, ‘This Side of the Grave: Navigating the Quaker Plainness Testimony in London and Philadelphia in the Eighteenth Century’ Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 49, No. 1 (2015), 40.

[7] E. Hanbury Hankin, Common Sense and Its Cultivation (1926), 266.