This guest post shows how one historian worked on a specific area of early Tudor history and one family throughout their lives. It explores both the importance of this work and the struggles the historian can face.

On 6 November 1538, a woman in her late forties named Honor Lisle boarded a ship at the stair of Calais. She hoped to meet her husband, Arthur Plantagenet, Viscount Lisle, at the docks, but he did not appear. This upset her. The wind was light. The vessel did not reach Dover until ten in the evening.

She told ‘merry tales’ to her attendants and the captain, named Lamb, while cooks made a shore supper. In the dark, Lamb had crashed the ship into a pier, breaking the bowsprit. The next day she left for London to attempt a meeting with Henry VIII. She wanted the King to fix a property lawsuit in her favour. She missed her husband. ‘I shall think every hour ten till I be with you again’, she wrote him.

We know all about the Lisles. We know about their beautiful daughters, their overworked servants, their friends and enemies, their money, their rich meals and garments, their fears and sicknesses, and their sleeping habits. We watch through the 1530s as they navigate Tudor politics and Lord Lisle moves closer and closer to arrest and imprisonment in the Tower.

We know the Lisles because a remarkable historian named Muriel St. Clare Byrne spent a lifetime deciphering, transcribing, and analysing their letters, moving to Tudor England in her mind and living with them like family.

The University of Chicago Press published the Lisle Letters – 1,677 documents in a million words, plus a million words of commentary by Byrne, in six volumes – in 1981.

Written or dictated by dozens of correspondents, sent mostly between London and Calais, mentioning hundreds of characters, the letters had been seized as evidence of possible treason in Lisle’s case and then mostly forgotten. Lisle was the bastard of King Edward IV, an uncle of Henry VIII and Lord Deputy of Calais, England’s last scrap of territory on the continent.

‘One of the most extraordinary historical works to be published in the century’, wrote The New York Times.[1] ‘We can really hear the people of early Tudor England talking’, wrote The Sunday Times. Commentators made comparisons with the works of Tolstoy, Proust, and Pasternak.

Even the most enthusiastic reviewers did not rave enough about Byrne’s personal accomplishment. How, without a professorship, living ‘at the margins of elite academic life’, [2] with almost no help or supervision, did she produce what Smithsonian magazine called ‘a landmark of twentieth century scholarship’?

Papers at the University of Chicago Library, where I spent a recent afternoon, show a determination and adoring love for her subject that carried her through decades of uncertainty, slights, and money shortages and then a brutal rejection when she thought she was almost done.

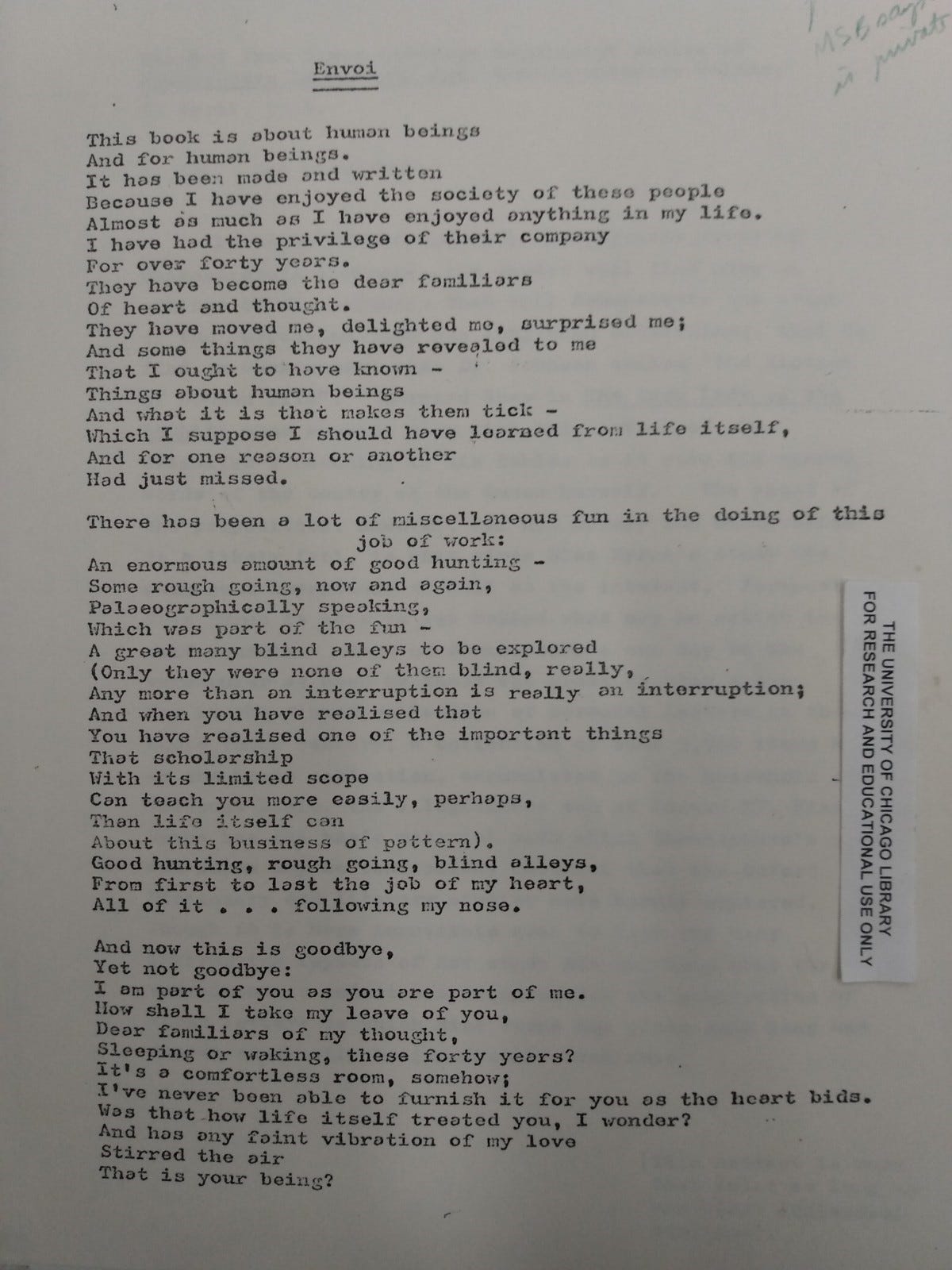

‘I have enjoyed the society of these people/ Almost as much as I have enjoyed anything in my life’, wrote Byrne near the end of the project in an unpublished farewell to the Lisles in the library’s Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections. ‘I am part of you as you are part of me. / How shall I take my leave of you, / Dear familiars of my thought, / Sleeping or waking, these forty years’?[3]

Byrne came across the Lisle Letters in the British Public Record Office in 1932. She had earned a master’s degree from Oxford’s Somerville College, making lifelong friendships described by Mo Moulton in The Mutual Admiration Society: How Dorothy L. Sayers And Her Oxford Circle Remade The World For Women.[4]

But Byrne’s gender and lack of a first-class honours degree kept her from becoming a university don. She took temporary teaching jobs and wrote popular history, publishing Elizabethan Life in Town and Country in 1925 and earning money from a 1936 detective play she wrote with Sayers.

During World War II she had to duck under the Public Record Office tables and abandon the Lisle research if bombers threatened. Her lover and lifelong partner, Marjorie Barber, knew Byrne would be spared for the Lisles. ‘I think you will be kept to finish them, like Churchill’, she wrote.[5]

By the 1950s Byrne was talking about publishing. ‘I am unshaken in my hope that you will at least allow me to make an oration on behalf of the Lisle Letters to my board’, T.S. Eliot wrote to her in July 1956.[6] The poet was an editor at publisher Faber and Faber.

T.S. Eliot to M. St. Clare Byrne, 26 July, 1956. Courtesy of Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

‘I am indeed delighted that we shall now get the Lisle Papers published’, historian G.M. Trevelyan wrote to her in 1955.[7]

‘I rejoice that you are now quite fit again and eager to finish your great work’, historian J. Dover Wilson wrote to her in 1964.[8]

‘The work… is now in its final stages’, wrote Professor A.G. Dickens in 1966, after Faber had finally agreed to publish.[9]

In fact, Byrne was stuck in the sixteenth century, absorbed in ‘an enormous amount of good hunting’, as she wrote in her unpublished envoi, going down ‘a great many blind alleys… following my nose’ and getting nowhere close to the final stages.

No personality was too obscure or removed from the Lisles to track down, link to associates and size up for personality and handwriting. Every writer deserved to be able to speak again. No financial dispute was too trivial to be adjudicated four centuries later.

Few paleographical puzzles (vmlyst spells humblest and frydstokefysche means fried stockfish) went unsolved. Honor Lisle’s request to Queen Anne Boleyn for an overdress called a kirtle is traced and analysed through nearly a dozen letters sent over the course of more than a year.

‘It would be idle to deny that Miss Byrne nearly kills her subject with love’, wrote The New York Times review.[10]

Maybe. But Byrne’s immersion produced a deep understanding of early-Tudor society – and ‘things about human beings’ generally, as she wrote – along with the confidence to guide her readers through this world.

Meanwhile, she was living off royalty crumbs and infrequent grants. ‘I note with sorrow her financial situation’, Wilson wrote in a draft recommendation for funds, in words redlined out of the final version.[11]

M. St. Clare Byrne, ‘Envoi’. Courtesy of Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

Faber editors were horrified when they finally realized what was going on. They backed out, quite confident that turning Byrne’s 5,700 single-spaced typed pages into a book was not a promising business venture.

‘When we made the original contract in 1965 we really had no clear idea of what the book was going to contain’, wrote a Faber executive a decade later.[12]

The University of Chicago Press came to the rescue. They had already been marginally involved and were better set than Faber to seek sponsorship for the project. Press Director Morris Philipson did brave work, raising $100,000 (about $500,000 today), arranging for the manuscript to be hand-carried from London by an acquaintance of Byrne’s and persuading the Crown to grant publishing rights for £25.

Byrne worked on the publication long distance and sought large and unreasonable changes in paragraphing and indentation. She was told in 1978 by the director Philipson that ‘those changes that you argue for, over and over again, are not going to be made’.[13]

Muriel St. Clare Byrne in suit. No date. Somerville College Library, Oxford [MSCBC 9/3] (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

The Lisle Letters came out in the spring of 1981, on Byrne’s 86th birthday.

‘Whenever I see her she is turning over the pages, purring over the layout, the reproduction and placing of the illustrations, the perfection of the index, how pleasantly the volumes look and handle’, Byrne’s friend Bridget Boland, who edited a one-volume abridgement published two years later, wrote to the Press. ‘If you had known her in the dark days when Fabers suddenly backed down you would not think her the same woman’.[14]

References and Resources:

Information for this post was taken from papers in the Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago.

Muriel St. Clare Byrne (ed.), The Lisle Letters: Six Volumes (1981)

Muriel St. Clare Byrne (ed.), The Lisle Letters- Abridged (1983)

J.H. Plumb, ‘Henry VIII Was The Man To See’, The New York Times Book Review, June 14, 1981

Mo Moulton, The Mutual Admiration Society: How Dorothy L. Sayers and Her Oxford Circle Remade the World for Women (2019)

Jay Hancock writes about history and society. He was the diplomatic correspondent and the economics correspondent for The Baltimore Sun. His articles have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post and elsewhere. In 2020 he was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in investigative journalism. His free Substack is here. He can be contacted on jayhancock@protonmail.com.

[1] J.H. Plumb, ‘Henry VIII Was The Man To See’, The New York Times Book Review, June 14, 1981, p. 9.

[2] Mo Moulton, The Mutual Admiration Society: How Dorothy L. Sayers and Her Oxford Circle Remade the World for Women (2019), p. 133.

[3] M. St. Clare Byrne, undated, Hanna Holborn Gray (hereafter HHG) Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago.

[4] Mo Moulton, The Mutual Admiration Society.

[5] Moulton, pp. 202-3, p. 222, p. 253.

[6] T.S. Eliot to M. St. Clare Byrne, 26 July, 1956, HHG Special Collections.

[7] G.M. Trevelyan to M. St. Clare Byrne, 9 May, 1955, HHG Special Collections.

[8] J. Dover Wilson to M. St. Clare Byrne, 11 Jan., 1964, HHG Special Collections.

[9] A.G. Dickens to a Miss Swainson, 28 April, 1966, HHG Special Collections.

[10] Plumb, ‘Henry VIII Was The Man To See’, NYT.

[11] J. Dover Wilson to unknown, 14 Feb. 1964, HHG Special Collections.

[12] Frank Pike to Morris Philipson, 3 February 1975, HHG Special Collections.

[13] Morris Philipson to M. St. Clare Byrne, 26 July 1978. HHG Special Collections.

[14] Bridget Boland to a Miss Richardson, 27 March 1981. HHG Special Collections.

The detail put into this is amazing. Thank you. 🙏🏻.

I own, and have read Boland's condensation. Among other aspects of the letters the Lisle's factor, business manager, confidant, emerges as one of literature's great characters. Also, the manner in which the family copes with recurring waves of plague - get out of London - has perhaps a special meaning for us today. And it emerges that the word 'merry' takes on a multiplicity of meanings; eg, The Merry Wives of Windsor does not mean that they're happy. Perhaps abebooks will have a copy? Well worth reading. As is this introduction. Thanks.