Exhibition catalogues are printed and sold to accompany displays in museums and galleries around the world. These catalogues come in a range of sizes from small, almost leaflet like printed guides, to large coffee-table books with glossy pictures and well thought through essays explaining the history of an item or section. This latter sort has become the most popular type of exhibition catalogue in recent years.

A selection of Exhibition Catalogues from museums and galleries in London © Anna Cusack

It was in the 1960s that, due to cheaper printing of colour images, the exhibition catalogue took off as a standard item to be sold accompanying exhibitions. Prior to this catalogues normally took the form of an unillustrated ‘checklist’. These would list the title of the work, dimensions, medium and creator. Today a lot of thought goes into the creation of exhibition catalogues and there is a creative process behind publication that aims to capture the feel of an exhibition.

…a good catalogue must nonetheless bring over something of the flavour, the temper, the attitude, the very feel of the show, while revealing something important to us about the nature of its subject. It has a duty, to a greater or lesser degree, to the onward march of scholarship.[1]

There is no real standard format to these catalogues, although they often start with an introduction written by the curator who oversaw the exhibition, or the museum/gallery director. Most follow the layout of the exhibition itself guiding the reader through each object and each room. They contain more detailed information about the items than what is on captions and what may be recorded of objects on permanent display in the museum or gallery. Many modern exhibition catalogues contain footnotes, bibliographies, an index, and several essays often written by experts on the exhibition subject. These include historians, archaeologists, artists, and staff from within the museum or gallery who specialise in that research area. If an exhibition tours multiple countries translators are employed to produce editions for each location.

When an exhibition catalogue comes from an exhibition that has been hosted at one of the large major museums and galleries around the world, they are normally published by the organisation itself which have their own publishing companies. Smaller institutions outsource their publications and, whether published in-house or externally, they are often sponsored by another organisation that supports the museum, gallery or the exhibition specifically.

Catalogue to the exhibition: Indigenous Australia enduring civilisation. Held at The British Museum in 2015.

Catalogues are not really meant to be read as you peruse the exhibition itself (the growing size and weight of some of them would also make this impractical). They are intended to be purchased afterwards as a memento of a visit to a temporary display, a memory of a moment in time when the creative forces of a whole team of specialists developed a temporary exhibit for education and enjoyment.

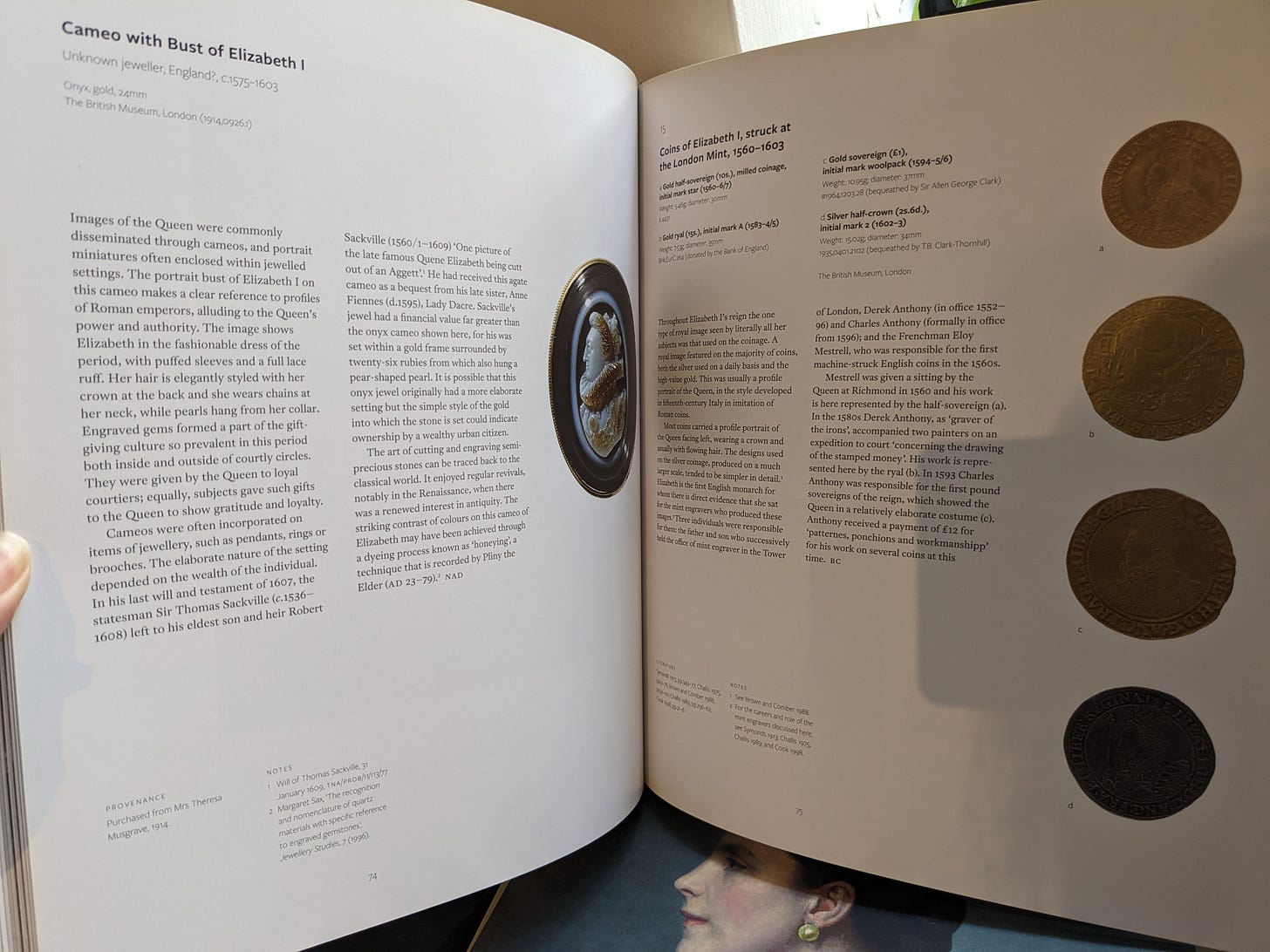

For historians, exhibition catalogues provide a unique resource, especially if your research deals with material and visual culture. Catalogues often contain the most up-to-date information and discoveries about a specific object and present the opportunity to get up close and personal with a historic creation. Take the below example from an exhibition that was held at the National Portrait Gallery in London in 2013/14 entitled Elizabeth I & Her People. The exhibition was about the Queen but also individuals who were present throughout her reign and so portraits and objects relating to these individuals were also on display.[2] In the exhibition catalogue below, we can see an entry for a cameo with a bust of Elizabeth I accompanied by text about the item, its provenance, notes, and a photo of the object. Likewise for Coins of Elizabeth I struck at the London Mint.

Elizabeth I & Her People. Exhibition catalogue, National Portrait Gallery.

Exhibition catalogues often have a limited print run and once an exhibition has been and gone it can be hard to get your hands on a catalogue. Luckily many museums and galleries now keep copies in their archives so they can be consulted by researchers. In London the British Library has copies along with other national libraries around the world.

Digitisation of exhibition catalogues, however, is still lacking although this seems like the next logical step and would make these wonderful resources more accessible. A few institutions have already attempted digitisation projects, including the Royal Academy of Arts Winter Exhibition catalogues, the Ashmolean collection catalogues, and a collection of catalogues published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Guggenheim. The Getty Research Portal provides free online access to an extensive collection of more than 100,000 digitized art history texts from a range of institutions, including many art catalogues.

The beauty of these catalogues is not simply in their content and glossy images, nor their short essays. It is also in their ability to bring the researcher back to a moment in time when they observed the items first hand and were transported back through history or into the mind of an artist through the works contained in their pages. Art historians have long understood the importance of catalogues, but the historian should also pay them attention. If nothing else, they look great on a coffee table.

References and Resources:

Gustavo Grandal Montero, Materials and collection management ‘Chapter 11. Art documentation: exhibition catalogues and beyond’ in Paul Glassman and Judy Dyki (eds.), The handbook of art and design librarianship. (2018)

Steven Lubar, A brief history of American museum catalogs to 1860. (2017)

Michael Glover, ‘What Are Exhibition Catalogues for?’. (2020)

Elizabeth I & Her People - National Portrait Gallery (npg.org.uk)

Royal Academy of Arts Winter Exhibition catalogues

[1] Michael Glover, ‘What Are Exhibition Catalogues for?’. (2020)

[2] Elizabeth I & Her People - National Portrait Gallery (npg.org.uk)