When we talk about Georgian fashion, we think of the fashions of the wealthy elite in the latter half of the eighteenth century, the people whose histories are more widely recorded. Up until the French Revolution at the end of the eighteenth century, at the heart of these fashion trends was wealth and the display of it. This would have been particularly true when it came to making an impression at court, where getting noticed by the royal family could lead to social improvement. At its height eighteenth-century fashion was impractical, extreme, and unrestrained, and trends often led to cultural shifts, satirised identities, and impractical styles. Hair reached new heights, makeup was lethal, and clothes became a barrier to comfort.

Fashions for women took time, products, and staff to create the perfect look that told everyone that you could afford it. Interestingly, wigs were not a huge female fashion trend. Hairstyles would largely be made of a woman’s own hair, perhaps with some extra false pieces when needed, styled over pads, and used powders and pomades to achieve the right look. Hairstyles were imposingly large, both tall and wide, and decorated with whatever ornaments the wearer wanted, including ribbons, feathers, flowers, and even fruit.. Makeup was also a time-consuming effort. It was largely common knowledge by this time that the lead in white face makeup was dangerous, but it did not stop everyone from using it to achieve the idealised pure-white face – a face that told onlookers that you had never had to commit yourself to manual labour out of doors. The perfect Georgian makeup look would have been accompanied with blush made out of family recipes used on cheeks and lips, darkened eyebrows, and beauty spots if the wearer wanted. Women’s clothes were also outlandish. In the mid-eighteenth century, a trend for women’s fashion emerged that would see skirts extending out a few meters from their sides. These impressive, if impractical mantua skirts would make it extremely difficult for women to walk through doors, sit down, and could use up to fourteen meters of fabric – another expensive expression of wealth.

Male fashion would often be just as gregarious as female fashions. It was common for men to wear styled wigs and make up. The most recognised fashions for men from this time would have been breeches and coats. Men’s breeches would go just below their knees, meaning that their stockinged calves would be on show. This led to a rather interesting brief fashion trend in the 1780s: Downy Calves. Padding would be stitched into stockings to create the impression of a bulkier calve, creating a more ‘masculine’ frame for the wearer. Men’s coats would either be formal or informal depending on the occasion. Informal frock coats would be less garish than their formal counterparts, which would often use expensive dyes to achieve bright colours and were expensively embroidered.

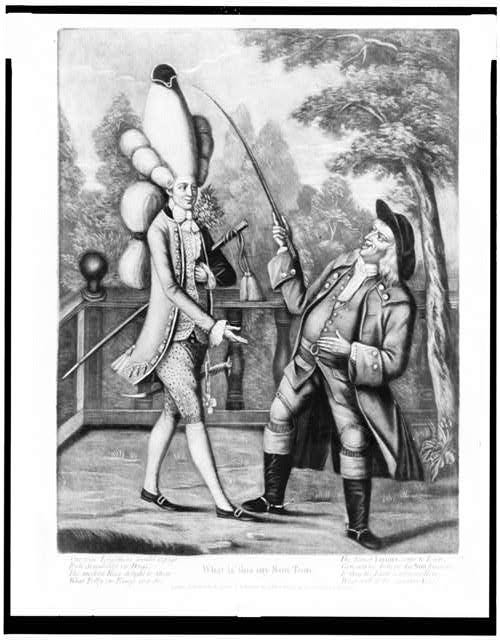

In the eighteenth century, men who were excessively concerned with their appearance and their clothing were known as Fops. The Fop was derided as an overfeminine man who would act with overly flamboyant airs and graces. The Fop would be a predecessor to the Macaroni, who took fashion trends to extremes and ‘exceeded ordinary bounds’ according to Amelia F. Rauser.[1] Macaroni wigs would often be so tall that they were comical, and they were often a source of satirical fun. The Macaroni was not a long-lived trend, and soon gave way to the Dandy in the early nineteenth century.

Macaroni Satire- ‘What! Is this my son Tom?’. Published by R. Sayer & J. Bennett, 1774. Public Domain

Anna Reynolds, Deputy Surveyor of The King’s Pictures, reminds us that ‘fashion reflects the changes of the period.’[2] No discussion of eighteenth-century society could miss out the events of one of the most seismic changes in early modern history. By the end of the eighteenth century, the effects of the French Revolution were being felt all over Europe. Britain was at war with France, but British nobles still strove to emulate French fashions. The radically changed country was had always been the epicentre of fashion trends and movements. The extravagant and ostentatious fashions that had ruled for much of the eighteenth century were foisted out, along with the people who wore them. These fashions were a reminder of how the affluent would flaunt their wealth through gaudy displays of fashion, perhaps by embroidering silver and gold into clothes, or by using jewels and expensive dyes, or using an unnecessary amount of fabric and lace. The remaining influencers in society were scarred and fearful that a return to this excess could result in more scenes like those witnessed during the Reign of Terror.[3] On top of that, war was an expensive undertaking, and the taxes imposed on the British to make it happen meant that there was less money for the type of free-spending that had been seen before the revolution.

Thomas Gainsborough, ‘Portrait of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire’. Between 1785 – 1787. Chatsworth House. Public Domain.

As a result, simplicity and under-indulgence became the latest trend. These emerging trends are the type of fashions we would recognise from adaptations of Jane Austen novels. Women would have been seen in dresses with higher waistlines, flat and more practical shoes, and simpler hair styles. Men would have been en-vogue in clothing that was also more suited to practicality: simpler outfits in less garish colours, boots more suitable for active pursuits, and definitely no wigs. Industrial innovations also meant that women’s simple dresses, often made out of cotton, could be mass-produced, meaning that there was a new and wider audience to consume these fashions. Georgian fashion was so lavish, but, in the end, they were superseded by trends that encompassed the complete opposite ideal. Some who were still prepared to spend lavishly on their fashion choices. The Prince Regent, later George IV, was known to spend excessively on all of his indulgences, his clothing and appearance included. This contributed largely to his continually declining reputation among the British people. Fashion had gone from being a way to clearly and explicitly show off your wealth, to being a symbol of simplicity and more modest living.

Rebecca Gadd is conducting her PhD on the underrepresented themes and topics present in the fictional works of Frances Burney (1752-1840) at Loughborough University. She has previously published articles on a wide variety of subjects, including Russian history, 21st century representations of female fairy tale villains, and is also currently working on eighteenth-century LGBTQ+ history.

X: @ramennresearch

Email: bexgadd95@hotmail.com

References and Resources:

Make-Up: A Glamourous History, Lisa Eldridge, BBC, 2021.

Robert Morrison, The Regency Revolution: Jane Austen, Napoleon, Lord Byron and the Making of the Modern World (2020).

Amelia F. Rauser, ‘Hair, Authenticity, and the Self-Made Macaroni’, in Eighteenth Century Studies, 38 (2004) 101-117.

‘Getting the Georgian Look’ by The Royal Collection Trust https://www.rct.uk/collection/exhibitions/style-society-dressing-the-georgians/the-kings-gallery-palace-of-holyroodhouse

‘How to Survive in the Georgian Court’ by Lucy Worsley for History Extra https://www.historyextra.com/membership/how-to-survive-in-the-georgian-court/

‘The Art of Dressing: Shaping Fashion in Georgian England’ by Lucy Ellis https://artuk.org/discover/stories/the-art-of-dressing-shaping-fashion-in-georgian-england

‘Bums, Tums and Downy Calves’ by Sarah Murden https://georgianera.wordpress.com/2014/07/22/bums-tums-and-downy-calves/

‘Dead Pretty: The Perils of Georgian Beauty Regimes’ by Jon Sleigh https://artuk.org/discover/stories/dead-pretty-the-perils-of-georgian-beauty-regimes

[1] Amelia F. Rauser, ‘Hair, Authenticity, and the Self-Made Macaroni’, in Eighteenth Century Studies, 38 (2004) 101-117.

[2] ‘Getting the Georgian Look’ by The Royal Collection Trust https://www.rct.uk/collection/exhibitions/style-society-dressing-the-georgians/the-kings-gallery-palace-of-holyroodhouse

[3] ‘The Art of Dressing: Shaping Fashion in Georgian England’ by Lucy Ellis https://artuk.org/discover/stories/the-art-of-dressing-shaping-fashion-in-georgian-england

Are we going to hear about where Beau Brummell fits in a later episode?