Early English anatomy manuals drew on the Italian style, specifically the Vesalian illustrations made available through the work of Thomas Geminus during the sixteenth century. Only a limited number of people would have had access to such manuals, namely Barber-Surgeons Company members, the College of Physicians and rich collectors from the upper spheres of society. Anatomy manuals were used as teaching aids and collectors’ items due to the expense in their production and use of Latin within the texts.

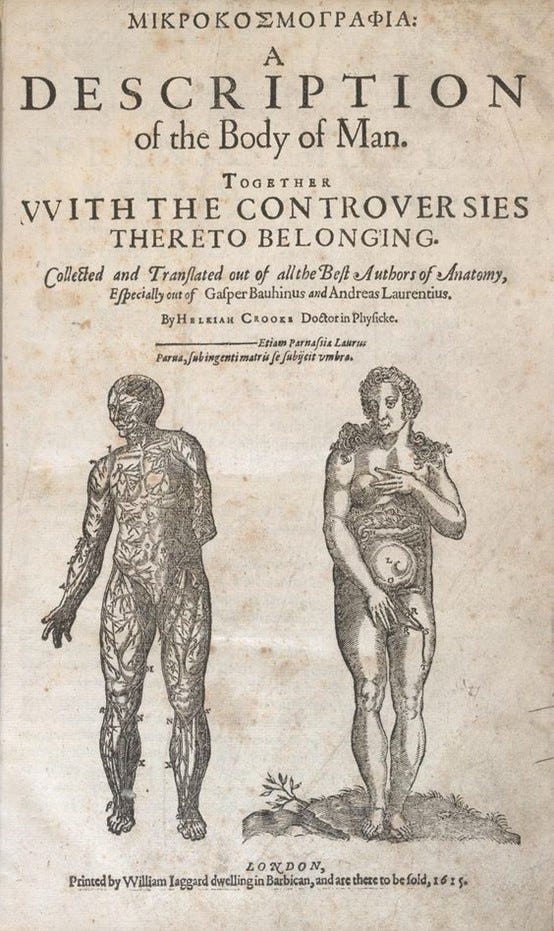

By the seventeenth century, Helkiah Crooke employed the style of Geminus and other artists in his own anatomical text Microcosmographia, first published in 1615. The image on the title page shows the difference in mentalities directed towards the male and female corpses. It depicts a completely écorché male figure, but the female figure is covering her sex and only her stomach is opened to the viewer so they can witness her reproductive function.[1] The female is posed in a classical style, almost modestly. The left hand is raised over the left breast but resting upon the right one. The straightening of the female’s fingers in the hand upon the right breast leads to the conclusion that she is presenting her breast to the viewers, who would have almost certainly been male.[2] This pose holds a similarity to images of the Madonna offering her breast to the infant Christ.[3] Another association that the female figure alludes to is the images of Venus, both the statue of Venus de’ Medici and Botticelli’s painting The Birth of Venus. Whether interpreted as the Madonna, Venus or as a seductress, the clear difference in the iconography is apparent.

Etching on the title page of Mikrokosmographia: A Description of the Body of Man. 1615 © The Trustees of The British Library.

Crooke’s book was highly controversial, not least because it was published in English and not Latin, but also due to the iconographic depictions, including the cover image. In 1614, the College of Physicians debated vernacular publication. Several thought that a few subjects and more indecent illustrations should be removed, and other points ought also to be corrected, while many considered that book four, with the pictures of the generative organs, should be ‘destroyed and that he [Crooke] should be enjoined to confess that it was a translation, that is of many subjects from Laurentius…and of…Bauhin’.[4] Crooke did eventually bow to some pressure and the second edition only depicted a flayed male figure in the process of dissecting himself on the front page.

Depictions of male figures performing dissections upon their own persons are of interest. There are no similar images of female figures in these poses and these types of images clearly display the living figure and not the corpse. Likewise, Alexander Read’s Somatographia anthropine, or A Description of the Body of Man originally published in 1616 was very similar in its iconographical depictions, again following the style set out by Andreas Vesalius in the late sixteenth century. Even by 1681 when John Browne published Myographia nova, or, A graphical description of all the muscles in humane body, as they arise in dissection, the depictions were all male, and again with figures dissecting themselves. Anatomists were not interested in the female muscular set it seems, and Browne, even as a surgeon who had performed many dissections, did not deem them relevant for inclusion in his study. These self-dissecting iconographic images are reminiscent of the story of Apollo and Marsyas as told in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Renaissance ideas of a Classical story were familiar enough to provide a dialogue which is why this particular style persisted for as long as it did.

John Brown, copperplate engraving showing muscles of the back and shoulder. © Wellcome Images.

Kate Cregan argues that a reason for staying in the Vesalian style, and in fact still using and re-engraving Vesalian woodcuts into the seventeenth century, was that it ‘described the sorts of eroticised overlay which those engravings drew with them in the depiction of the female body’. These images were impressed on the minds of observers and the public who witnessed anatomy demonstrations. Their use propagated the idea that ‘the gendered, cultural, gestural and aesthetic codes that are present in these representations of the body are in fact essential’.[5]

After Browne’s work, anatomical illustrations changed. William Cowper’s 1698, The Anatomy of Humane Bodies with Figures Drawn After the Life by Some of the Best Masters in Europe depicts the female figure in a way never seen in England before. The first two images of female bodies are similar to earlier manuals, but the other five images of the female body were far more detailed. If Cowper’s claim that the images were drawn from life is indeed true, there is a possibility they were drawn from female criminal cadavers.

The images in Cowper’s manual were drawn by Gerard de Lairesse and had been used in another, slightly earlier, Dutch work. Cowper unmistakably plagiarised that earlier work, but the images resonated with the English just as much as the Dutch and for the first time we see a move away from the Vesalian illustrations. Until the end of the seventeenth century, the images in anatomy manuals were clearly portrayed as those of living figures not images of a dead cadaver.

When Matthew Baillie published his anatomy manual in 1799 the anatomical illustrations had greatly changed.[6] They no longer depicted a living person as a corpse and instead portrayed dismembered body parts.

References and Resources:

H. Crooke, Mikrokosmographia. A description of the body of man: Together with the controversies thereto belonging (1631)

A. Read, Somatographia anthropine, or a Description of the Body of Man (1616)

K. Cregan, ‘Teaching the Anatomical Body in Seventeenth-Century London’, Medicine Studies, Vol. 2 (2010)

K .Cregan, The Theatre of the Body: Staging Death and Embodying Life in Early-Modern London (2009)

[1] écorché meaning a painting or sculpture of a human figure with the skin removed to display the musculature.

[2] K .Cregan, The Theatre of the Body: Staging Death and Embodying Life in Early-Modern London (2009), 88.

[3] C. Walker-Bynum, Fragmentation and Redemption: Essays on Gender and the Human Body in Medieval Religion (1991).

[4] J. Sawday, The Body Emblazoned: Dissection and the Human Body in Renaissance Culture (1995), 225.

[5] K. Cregan, ‘Teaching the Anatomical Body in Seventeenth-Century London’, Medicine Studies, Vol. 2 (2010), 30.

[6] Mr. Clift’s original drawings for Dr. Baillie’s work on morbid anatomy [RCP MS-BAILM/103/1-27]; M. Baillie, A Series of Engravings accompanied with explanations which are intended to illustrate the morbid anatomy of some of the most important parts of the human body (1799).

Wonderful, this made me think of two authors and their delightful arguments.

First, Laqueur in Making Sex and Solitary sex makes an insightful argument regarding how ideas about bodies and sex gave anatomists a certain gaze that shaped how they saw what they dissected. When we look at some of these anatomical drawings today (with a different gaze) we see something altogether different. He contended that certain anatomical features are drawn resembling others because of ideas about bodies held at the time -- thus Vesalius's drawings of reproductive organs resemble one another. In fact they used similar terms for organs like testes and ovaries -- which Laqueur sustained suggest they saw them as analogous or similar.

The other is a book by Kuriyama where he tracts the history of medicine in the east and the west. One of the striking things about Western anatomical drawings is the presence of muscles and musculature. In contrast, anatomist of the east, drew transparent bodies with other stuff flowing in and out of them. The former was a result of a connection of the muscular will with free will whereas in the East the body is seen as more porous and under the effects of the outside.