In Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Man with the Twisted Lip, Sherlock Holmes speaks to Watson of a ‘rascally Lascar’ who runs an opium den in the East End of London. Holmes describes the lascar as ‘one of my natural enemies, or, shall I say, my natural prey,’ and, who he later adds, ‘has sworn to have vengeance upon me.’ At the same time, however, despite his animosity with Holmes this lascar was not without friends in London—but I cannot possibly delve into that without giving spoilers!

A lascar, simply put, was a seaman of mostly South Asian origin— ‘mostly’ because there were a few instances when a specific group of Arabian (if from the Aden Colony in Yemen), East African (Somali), or Southeast Asian (like Malay) seamen could have also been categorised as lascars, whereas Chinese sailors were seemingly a different category altogether. Described as the first proper ‘globalised workforce’ by Gopalan Balachandran, lascars made the inter-oceanic commerce of the British Empire possible, while their identities and roles remained highly contested and fluid.[1] Although lascars did not just work on British ships but rather for any shipping company willing to hire them, and while as a workforce they were active between the sixteenth century at the earliest till about the 1970s, many of those who became lascars belonged to seafaring communities which had antecedents of shipboard labour with a far longer history..

The study of lascars began from the work of Rozina Visram, which explored their harsh working conditions and racially motivated social and legal discrimination imposed by the state, as well as community-formation and settlement in Britain.[2] For a while afterwards there seemed to have been little discussion regarding working-class Indians located in the context of mainland Britain or its empire. A relative surge in interest on lascars has largely been a very recent phenomenon, which includes Sumita Mukherjee’s ongoing funded project titled Remaking Britain: South Asian Networks and Connections, 1830s to the Present at the University of Bristol, as well as Yasmin Khan’s 2018 BBC documentary A Passage to Britain.[3] Among others, Balachandran’s study demonstrated how important lascar labour was in the context of European merchant shipping through an examination of the recruitment, control, social and regional composition, working conditions, voyages, as well as patterns of resistance relevant to lascars. Meanwhile, Aaron Jaffer has also provided a pioneering study examining the dynamics of mutinies perpetrated by lascar crews in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[4]

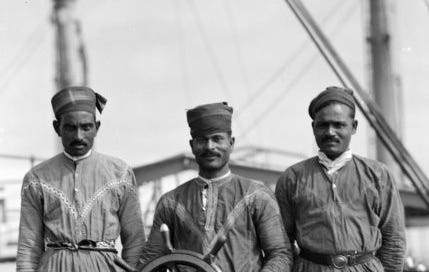

Three Lascars standing behind the wheel on board one of the motor tenders of the Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company cruise ship Viceroy of India (1929), National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. [RMG reference: P85233]

Although not specifically focussing on lascars but rather colonial seamen in general, Laura Tabili’s research on workers and racial difference in the late imperial period has been very insightful on how ideas of race were constructed and sustained, especially in terms of how notions of race were used by the shipowners and unions to their own advantage and how ‘black’ seamen were ‘recolonised’ when ashore by withholding economic, political, and social rights white British subjects enjoyed.[5] Her equally influential work on the Coloured Alien Seamen Order of 1925 observes the institutionalisation of racial discrimination as a part of British state policy by classing ‘coloured’ seamen as ‘aliens’ in lieu of a racially-fabricated notion of nationality and what it meant to be ‘British’.[6]

However, a lot more remains to be studied and said about lascars, considering the impact they have had on both their countries of origins as well as Europe and even North America—all the while acting as agents of socio-economic transformation while navigating within oppressive systems. This is true of aspects which went far beyond just physical labour, and even extended to the global politics of the twentieth century—as can be seen through the creation of International Seamen’s Club or ‘Interclubs’ in places like Hamburg as studied by Holger Weiss, or the political expressions of what has been termed ‘subaltern internationalism’ by Naina Manjrekar, or even what Ali Raza and Benjamin Zachariah have come to argue was the ‘lascar system’ of political networks.[7]

In fact—and returning to Sherlock Holmes’s ‘rascally Lascar’ from earlier—many recent studies have also focussed on how lascars in their capacity as a highly mobile workforce were crucially involved in transnational smuggling networks of the modern world. Jonathan Hyslop has suggested that by the late 1920s, lascars had not only been successful in setting up an international small-scale arms trade, but also in creating global networks in which guns and drugs circulated reciprocally.[8] James H. Mills has presented further evidence of lascars passing through British ports who were smuggling cannabis into the country for sale, while I have recently shown elsewhere what might have been indicative of a smuggling network for revolutionary literature between the USA and India in the aftermath of the creation of the USSR.[9] In any case, as the Sherlock Holmes story shows, opium dens run by lascars may have been operating in Britain as far back as the Victorian period.

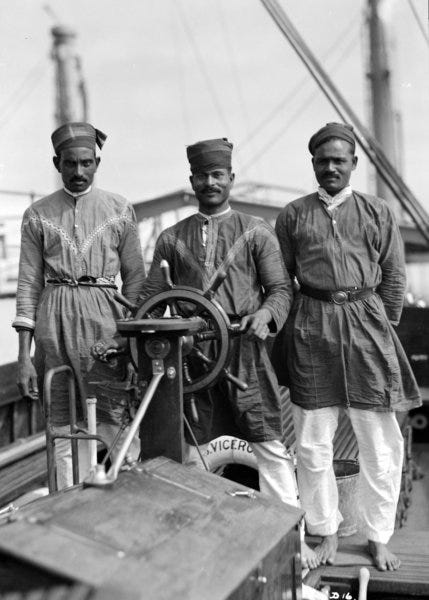

SS Chyebassa, a merchant ship of the British India Line, 1917. P & O Collection of Merchant Navy Photographs. Imperial War Museum [Reference: Q 94607]

Moreover, at a time when the mobility of South Asians was severely restricted by the imperial state, a lascar deserting his ship while ashore in Britain was the best chance a colonial subject with limited resources and education had of settling down in Britain in hopes of a better future. To sustain themselves in a foreign land, they would often shift to itinerant petty trading—at times even delving into peddling illegal substances. This is despite, as Ravi Ahuja has argued, the fact that the lascars’ extraordinary mobility was still restricted by both legal and extra-legal means, mainly because of the shipowner’s vested interests. While Vivek Bald has studied lascars settling down in the USA, David Holland has been one of the only academics to study those who did so in Britain and ventured into itinerant petty trading.[10]

At the time of writing this, the latest contribution to the topic of lascars has been an analysis of caste-based hierarchies and tensions within lascar crews—an aspect which had been hitherto overlooked. This indicates how much there is to uncover here in the context of the histories of both Britain and the world.

Shagnick Bhattacharya is a recent graduate from the University of Exeter where he has completed an MRes in Economic and Social History. His dissertation, titled ‘Indian Seamen and the Empire: “The Lascar Problem” in Interwar Britain’ explored the political activities and economic value of lascars during the interwar period, their occasional desertions and settlement in Britain, as well as the public perception of lascars at the time based on racially-coloured media discourses.

References and Resources:

Hossain, Ashfaque. “The world of the Sylheti seamen in the Age of Empire, from the late eighteenth century to 1947.” Journal of Global History 9 (2014): 425–446.

Sherwood, Marika. “Race, nationality and employment among Lascar seamen, 1660 to 1945.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 17:2 (1991): 229-244.

Visram, Rozina. Ayahs, Lascars and Princes: The Story of Indians in Britain 1700-1947. Pluto Press, 1986.

Bhattacharya, Shagnick. “Shipboard Labour and Caste in the Twentieth Century.” History Workshop (2025): historyworkshop.org.uk/labour/shipboard-labour-and-caste-in-the-twentieth-century/.

Bhattacharya, Shagnick. “Century Tales: Subaltern Smugglers from South Asia”, LSE South Asia Blog (2025): blogs.lse.ac.uk/southasia/2025/01/06/century-tales-subaltern-smugglers-from-south-asia/.

Nick Messinger’s The Old Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company, c.1835-1972 (https://pandosnco.co.uk/).

Open University’s Making Britain database (open.ac.uk/research-projects/making-britain/search/node/lascar).

“Looking for Lascars in the Archive: Non-European Seamen in Ship’s official Logbooks.” By Naina Manjrekar. 8th March 2022, Memorial University of Newfoundland:

“‘Citizens’ or ‘Aliens’? Lascar settlement in Britain (1900-1946).” By Naina Manjrekar. 9th October 2016, Idea Store Whitechapel, East London, UK:

“Lascars.” By Heloise Finch-Boyer and Tracey Weller. 22nd October 2014, Idea Store Whitechapel, East London, UK:

“Reimagining the Victorian East End: Islam, Lascar Seafarers and Subaltern Histories.” By Shahida Rahman and Nazneen Ahmed. 27th April 2013, Rich Mix Centre, East London, UK:

[1] Gopalan Balachandran, Globalizing Labour? Indian Seafarers and World Shipping, c. 1870- 1945, (Oxford University Press, 2012).

[2] Rozina Visram, Ayahs, Lascars and Princes: The Story of Indians in Britain 1700-1947 (Pluto Press, 1986).

[3] A Passage to Britain (Episode 1: The Viceroy of India), directed by Yasmin Khan, BBC Two, 2018. See https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0bg6vg3.

[4] Aaron Jaffer, Lascars and Indian Ocean Seafaring, 1780-1860: Shipboard Life, Unrest and Mutiny (Boydell & Brewer, 2015).

[5] Laura Tabili, ‘We Ask for British Justice’: Workers and Racial Difference in Late Imperial Britain (Cornell University Press, 1994).

[6] Laura Tabili, “The Construction of Racial Difference in Twentieth-Century Britain: The Special Restriction (Coloured Alien Seamen) Order, 1925,” Journal of British Studies, Vol. 33, No. 1 (January 1994).

[7] See Holger Weiss, “‘Unite in International Solidarity!’ The Call of the International of Seamen and Harbour Workers to ‘Colonial’ and ‘Negro’ Seamen in the Early 1930s,” in The Internationalisation of the Labour Question, eds. S. Bellucci and H. Weiss (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019); Naina Manjrekar, “‘To shake hands across the ocean’: the political worlds of South Asian seamen, c.1918‐ 1946” (PhD diss., SOAS University of London, 2018), 83-139; and, Ali Raza and Benjamin Zachariah, “To Take Arms Across a Sea of Trouble: The ‘Lascar System,’ Politics, and Agency in the 1920s,” Itinerario vol. XXXVI, issue 3 (2012).

[8] Jonathan Hyslop, “Guns, Drugs and Revolutionary Propaganda: Indian Sailors and Smuggling in the 1920s,” South African Historical Journal, 61:4 (2009).

[9] For cannabis smuggling, see James H. Mills, “‘Frost is the only thing which kills it’: Lascars, the Drugs Branch, and Doctors, c.1928–c.1945,” Cannabis Nation: Control and Consumption in Britain, 1928-2008 (Oxford University Press, 2012). For the specific smuggling network between India and the USA mentioned here, see Shagnick Bhattacharya, “Century Tales: Subaltern Smugglers from South Asia”, LSE South Asia Blog (2025).

[10] See Ravi Ahuja, “Mobility and Containment: The Voyages of South Asian Seamen, c.1900–1960,” International Review of Social History 51, no. S14 (2006): 111–41; Vivek Bald, “Overlapping Diasporas, Multiracial Lives: South Asian Muslims in U.S. Communities of Color, 1880 1950,” Souls, 8:4 (2006); David Holland, “Toffee Men, Travelling Drapers and Black-Market Perfumers–South Asian Networks of Petty Trade in Early Twentieth Century Britain,” Twentieth Century British History, Vol. 30, No. 2 (2019); and “The Social Networks of South Asian Migrants in the Sheffield Area During the Early Twentieth Century,” Past and Present, no. 236 (2017).

Great post. I wrote around the topic of travel in the early 20th century in general https://lila.substack.com/p/so-youre-on-a-1900s-steamship?utm_source=publication-search