London’s Parish Plague Records

London

Most people know about the ‘Great Plague’ of London in 1665 and tend to connect this to the ‘Great Fire’ in the following year. Fewer people are aware that London experienced several epidemics of plague in the seventeenth century - 1603,1625, 1636, and 1665 - and runs of years in which the disease was present in endemic form - 1604-11, 1630-31, and 1637-48. Plague was a long-term problem, and in tandem with poverty, created ongoing problems for Londoners, particularly those living in the fast-growing suburbs outside the city walls.

The impact of and response to plague in early modern London reveals much about the transformative growth and development of the capital in this period, for which we are lucky enough to have an array of useful sources. These include national and civic records, from which we can glean insights about the central response to plague. The Bills of Mortality were a weekly return of all burials and baptisms in each London parish, which included the number of plague burials. Where they do survive, arguably, the most illuminating records are those of London’s 120 or so parishes. These records are not without limits, but given the responsibility placed upon parishes to implement the Plague Orders, they take us to the frontline of plague events.

The English Plague Orders were the result of local experiments with plague regulations and were influenced by measures developed on the continent. They were codified in 1578 and received statutory sanction in 1604. These regulations remained relatively unchanged until a major revision in 1666. On account of its growing size and problems with plague in the decade or so following a major epidemic in 1563, London received its own special set of regulations in 1583. The responsibility of the parish to implement them was set out from the start, and although this placed the burden at the door of parish governors, it also presented the power and flexibility to respond to local problems as they arose. This was mirrored by the application of the Poor Laws at the local level and how the management of the poor and plague intersected.

The working of the Plague Orders at the local level generated an assortment of administrative sources. These include churchwardens’ accounts and other assorted accounts associated with the collection of rates and payments to the poor and poor visited (with plague), vestry minutes, and although set down by a different and much earlier statute, burial registers.

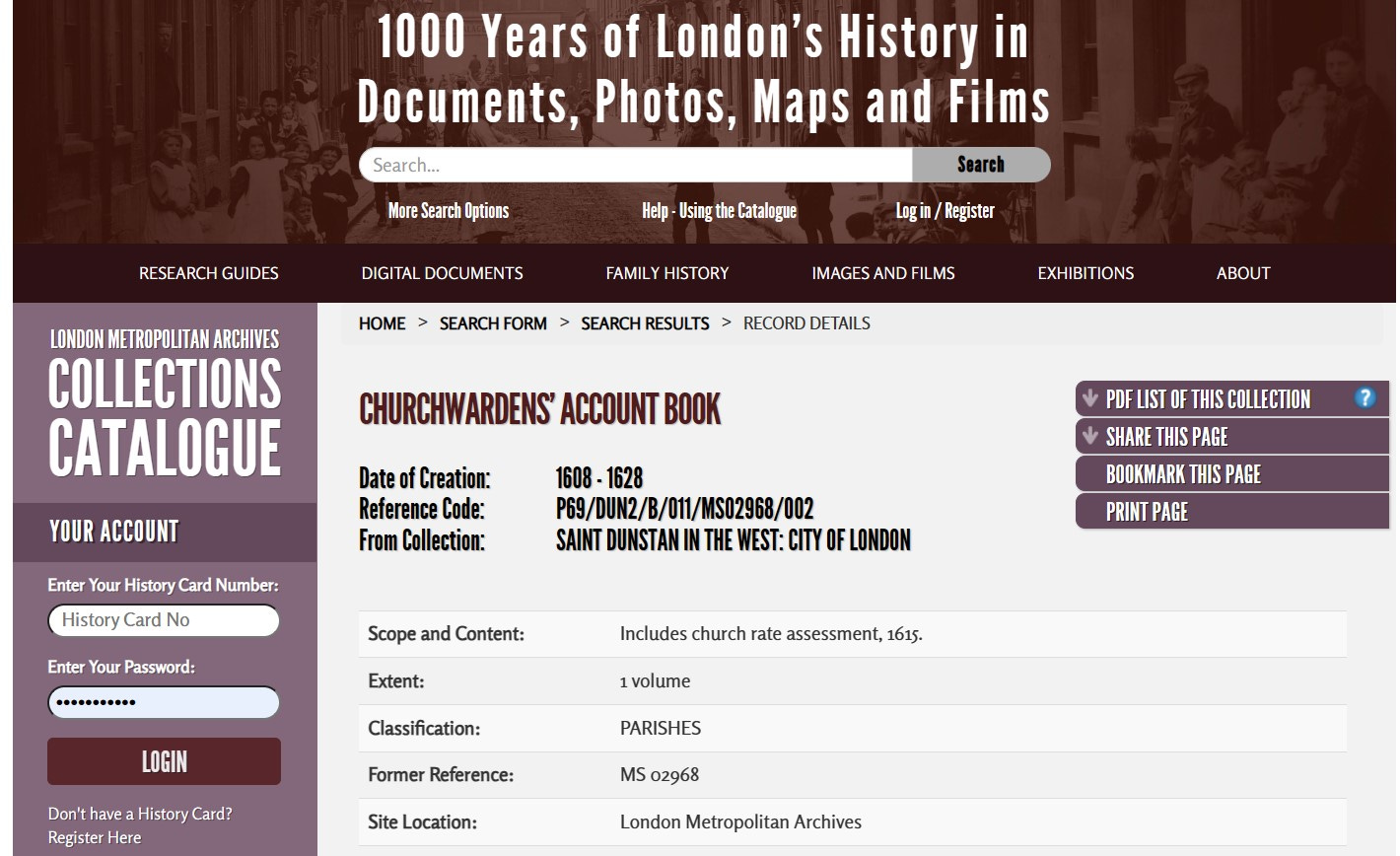

The records of the parishes under the jurisdiction of the City of London are held at the London Metropolitan Archives in Clerkenwell, and in most cases, the manuscripts themselves can be accessed. These are searchable online, are well catalogued, and can be booked before a visit.

A catalogue description of P69/DUN2/B/011/MS02968/002, the Churchwardens’ accounts (1608-28) for St Dunstan in the West, a suburban parish in the western area outside the city walls

Although jurisdictionally separate, this was a period in which the built environments of London and Westminster had become contiguous. The records of the parishes in Westminster are held at the Westminster Archives Centre.

The recording of burials, marriages, and baptisms by parishes was required by statute from 1558. Burial registers record the burial of individuals by the parish, usually in the parish’s burial ground. They can be used to assess the number of people who died of plague during a particular event. Although some parish clerks marked plague burials in the register, this was not the norm. Estimates can be rendered by calculating burials above normal levels and cross-referencing with other parish sources that show that plague was present in the community. The manuscripts can be accessed at LMA but are also available digitally on Ancestry.com.

Beyond burial records, the working of the Plague Orders necessitated account keeping, such as that of the churchwardens and the parish officers charged with collecting and disbursing special plague rates. The recorded details vary between parishes, but they might record the individual households shut up and supported by the parish. The isolation of an entire household, both sick and healthy, was the key tenant of plague regulations, and parishes were required to support those who could not afford to support themselves in their quarantine. The level of detail about each quarantined household will vary between parishes, or even within the parish, as a common format was not set down and some clerks were more fastidious than others.

Entries in a special St Sepulchre Newgate account book for the management of plague in 1647. LMA P69/SEP/ B/123/MS09080/001B – not foliated. Not to be reproduced.

The accounts also reflect the more general plague spending of the parish. This could include the burial of the poorer members of the community, the payment of plague auxiliaries such as nurses, searchers, and those paid to watch the shut-up houses, or even the purchase of fragrant herbs to cleanse the air of the parish church, alongside a plethora of other expenses. Although mostly absent during minor plague events, the accounts can also show any sums paid to the parish by the City to support their plague-time work. Accounts are incredibly useful as they show the practical application of the plague regulations and the specific ways that parishes responded to the disease.

Vestry minutes are also useful, and when possible, are best used in tandem with churchwardens' accounts. The vestry was the secular group of men who governed the parish. Their composition reflected the elite of the parish. They met regularly to discuss parish business and were responsible for seeing the Poor Laws and Plague Orders implemented, alongside the more general management of the parish. The vestry minutes are the collated record of their meetings and show the process by which decisions were made. As with the churchwardens’ accounts, they would have been written up from a series of rough records. It is worth noting that they also reflect what the vestry wanted to commit to the record and memory of the parish.

There are limits to the parish sources, principally, that no parish contains a perfect set of records. Survival is patchy, but when taken as a whole, the survival of the sources is quite remarkable. As commented, the perspective of these sources is that of the parish elite, which naturally contains their biases. An unsurprising issue with the records is the impact that the major epidemics had on record keeping, which might fall away through the worst of an epidemic. Finally, with the introduction of the Poor Laws, and alongside the Plague Orders, parishes became more meticulous in their record keeping through the first half of the seventeenth century. This usually means that the records are more detailed after 1630 or so than prior. With these caveats in mind though, the parish sources are essential to the study of plague in early modern London.

Aaron Columbus completed his PhD at Birkbeck, University of London. His thesis was focused on the response to plague and the poor in the suburban parishes of early modern London. Aaron recently worked as a Teaching fellow at Te Herenga Waka - Victoria University of Wellington and is Deputy Principal of Teaching and Learning at Wellington College. He continues to research and write about plague in early modern London. Find him on X @columbus_aaron or email him at aaron.columbus.phd@gmail.com

References and Resources:

Map of London parishes under the jurisdiction of the City of London

Helpful studies to show how parish sources can used to research plague in early modern London:

Vanessa Harding, ‘Burial of the plague dead in early modern London’ (1993)

Kira Newman, ‘Shutt Up: Bubonic Plague and Quarantine in Early Modern England’ (2012)

Aaron Columbus, ‘Plague pesthouses in early Stuart London’ (2021)

Jonathan Willis, ‘Understanding Sources: Churchwardens’ Accounts’ (2016)