Many European cultures have historically celebrated the first day of May, or the point between the spring equinox and summer solstice. This celebration has various forms including May Day, Beltane, Walpurgis Night and Calan Mai. It is a festival with a long past. In ancient Rome between 28 April and 1 May, the celebration of Floralia (Festival of Flora) was held in honour of the goddess of flowers, fertility, and spring. It involved athletic games and theatrical performances. In some places these games and theatrics continued in different forms. In Britain there are references to the ‘bringing-in of May’ as far back as 1240, though celebrations date from much earlier.[1] Gaelic tradition celebrates the ‘Fire of Bel’ or Beltane by lighting bonfires to welcome the new season. In Wales Calan Mai or Calan Haf was historically marked by bonfires, singing, dancing and other customs.

Pieter Brueghel the Younger, St. George's Kermis with the Dance around the Maypole. Seventeenth Century. Public Domain

Like many festivals, May Day celebrations were sometimes inversions of society. English towns and villages would elect a Lord and Lady of May from their inhabitants. Eventually this became the May Queen. By the nineteenth century, a young girl would be dressed in white accompanied by other young girls wearing flowers and wreaths and she would be crowned Queen of the May.

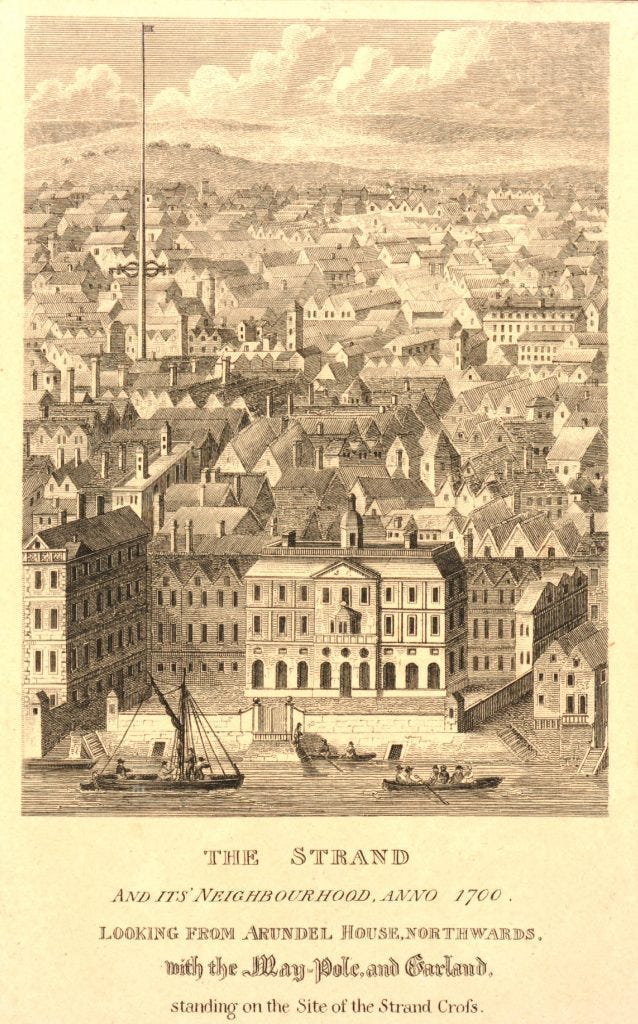

Maypoles are one of the most well-known practices associated with May Day in Europe. Perhaps the most famous, prominent, and largest maypole stood in front where the church of St Mary le Strand, London now stands. The first recorded maypole here was erected in the sixteenth century and is believed to have been around 100 feet high. On May Day the pole was decorated with flowers and surrounded by dancers from the early morning until the late evening. It was an important place all year round however, becoming the site of the first Hackney Carriage stand in 1634 and proudly depicted on the trade tokens of surrounding businesses. The maypole was destroyed in 1644 during the iconoclasm of the Civil Wars, being called one of the ‘last remnants of vile heathenism, round which people in holiday times used to dance, quite ignorant of its original intent and meaning’.[2] At the Restoration Charles II ordered a new maypole erected on the same site. This new maypole was reported to have been 135 feet high. Over the years it gradually decayed and so was replaced again in 1713.

Bird's eye view of the Strand from the River Thames, looking from Arundel House northwards, with the Maypole and Garland. Etching © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

In 1717 Sir Isaac Newton purchased the Strand maypole and had it removed, it is believed it was then used to support his telescope, the largest in the world at the time.[3] Maypoles were often reused. The maypole at Castle Bytham, Lincolnshire, was later cut in half for use as a ladder.

Carved inscription on a ladder in St James' church, Castle Bytham, Lincolnshire, which reads ‘THIS WARE THE MAY POVL 1660’, suggesting that the maypole was set up in the village to celebrate the Restoration of the Monarchy. Photograph © Simon Garbutt.

May Day celebrations continued throughout the Victorian and Edwardian eras. May flower baskets and sweet treats were left on neighbours’ doorsteps although this tradition has faded away, yet maypole dancing, crowning a May Queen and other celebrations continue in some places. Traditions can be very localised. May Day traditions in southern England include,

the Hobby Horses that still rampage through the towns of Dunster and Minehead in Somerset, and Padstow in Cornwall. The horse or the Oss, as it is normally called is a local person dressed in flowing robes wearing a mask with a grotesque, but colourful, caricature of a horse.[4]

In the nineteenth century the first day of May was designated International Workers’ Day and set aside for organised industrial agitation by socialist and trade union movements across the world. In 1978 the May Day Bank Holiday was instituted in the United Kingdom by the Labour government to mirror similar public holidays elsewhere.[5]

References and Resources:

John Chu, The history of May Day | National Trust

W. Thornbury, ‘St Mary-le-Strand and the Maypole’, Old and New London: Volume 3 (1878)

B. Jonson, May Day Celebrations (historic-uk.com)

R. Hutton, The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain (1996)

[1] R. Hutton, The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain (1996), 226. This 1240 reference was a complaint by the Bishop of Lincoln, Robert Grosseteste.

[2] W. Thornbury, ‘St Mary-le-Strand and the Maypole’, Old and New London: Volume 3 (1878), 84-88.

[3] Ibid.

[4] B. Jonson, May Day Celebrations (historic-uk.com)

[5] John Chu, The history of May Day | National Trust