Monsters

The World

The word 'monsters' is derived from the Latin monstrare, 'to demonstrate', and monere, 'to warn'. Though these fantastical creatures may take on any number of forms they all fundamentally stand as cyphers for something their creators deem terrible. Wherever they appear, monsters act as embodiments of those things that humanity should fear, whether that be the predations of dangerous animals, severe weather, perilous environments, or other people. Often these creatures lurch from the annals of ancient mythologies with warnings against the treacherous seas such as the hideous Scylla with which Odysseus must contend in the Odyssey, other times they are constructed monstrosities, built from the imagination as a way of tarring the reputation of feared individuals or marginalised peoples. In pre-modern times especially, when many of these creatures were believed to be real, appearing in the annals of natural history, their power upon the imagination was only heightened. Studying monsters, therefore, can be of great interest to the historian as symbols of the anxieties of those who made, and were terrified by them.

J.R.R. Tolkien can be considered the father of 'monster studies'. Highlighting in 1936 the centrality of the monsters of Beowulf, he argued that: ‘A dragon is no idle fancy. Whatever may be his origins, in fact or invention, the dragon in legend is a potent creation of men’s imagination, richer in significance than his barrow is in gold.'[1] Tolkien ultimately questions, why we imagine such creatures, and what they represent to those who conjure them. Since Tolkien’s work the study of monsters has flourished, especially within literary circles where these imagined creatures have long held significant narrative substance in their unnatural forms. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen in the 1996 edited collection Monster Theory: Reading Culture offers several theses for the pursuit of monster studies that are as applicable to the literary scholar as they are the historian: the monster is born of the culture that creates it, sitting at a crossroads resisting easy classification as a dialectic 'other' who polices boundaries, draws attention to difference, and challenges norms.[2]

For the historian, answering the questions of why we imagine monsters and what they represent reveals the anxieties of a given culture. Fortunately for us, the people of the past conjured many such creatures across a wide spectrum of sources. Initially, we might look to folklore, mythology, religion, and art for these creatures. Indeed, monsters are plentiful in all these sources as cyphers for abstract concepts, including, but not limited to, the nature of evil or the dangers of the wilderness. Monster can, however, also be found in architecture, satire, political treatise, heraldry, relics, scientific discourse, medical works, broadsheets, and amongst other sources where they can represent a host of different, and often fairly specific, concepts. Their capacity to embody feared and hated ideas make them especially malleable for expressing the anxieties of societies who imagine them.

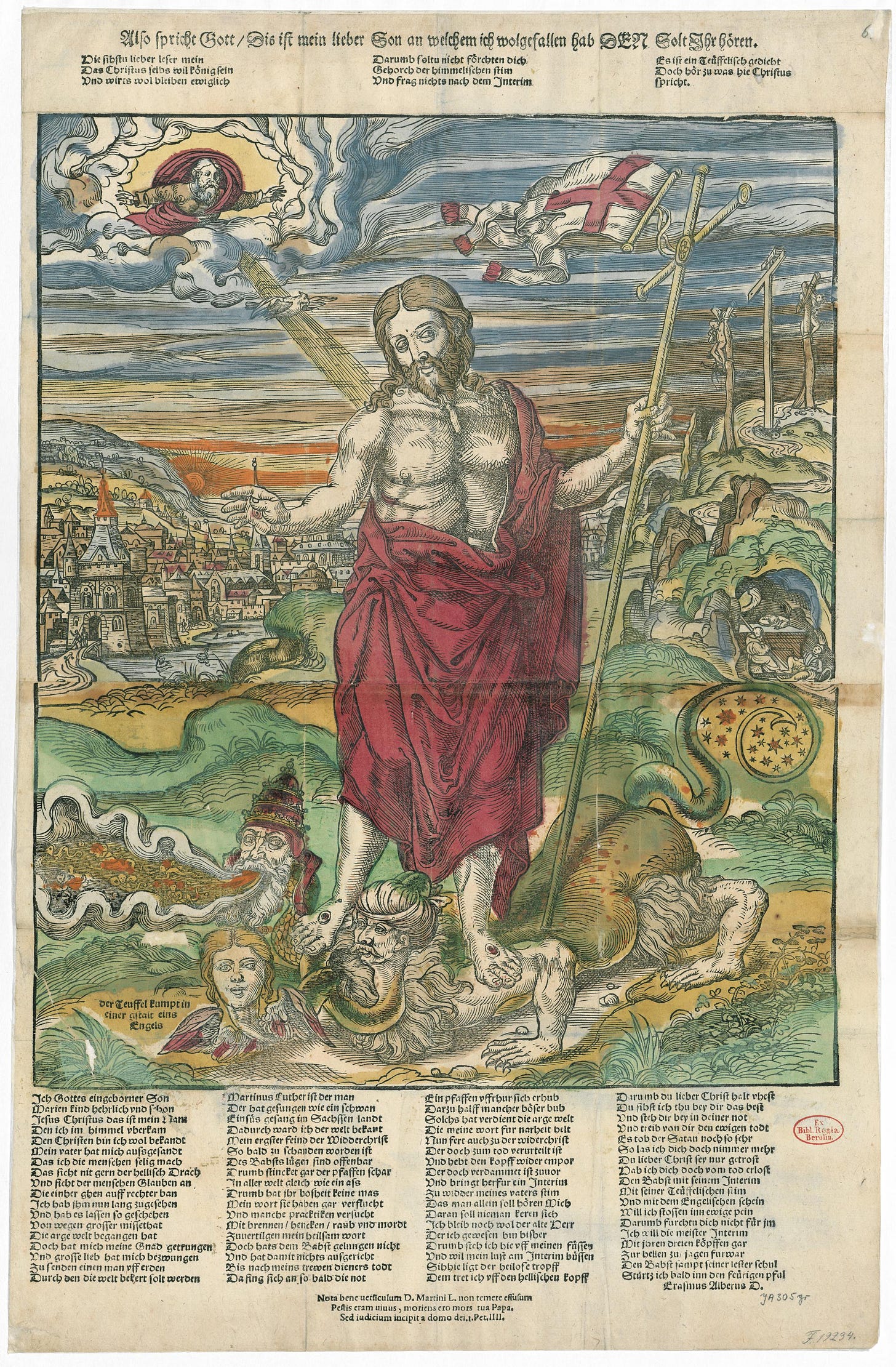

Christ Defeats the Pope as Three-headed Beast, Magdeburg, c.1550. (https://www.loc.gov/item/2021670763/. World Digital Library).

Indeed, one source base especially replete with monsters is the print culture of the early modern Religious reformations. Some of these creatures were expressions of religious uncertainty and criticisms of religious institutions, such as Martin Luther's famous Monk-Calf–an alleged monstrous birth of a malformed calf whose odd folds of skin resembled a monk's cowl–that seemed an omen of God's judgement.[3] Less subtle were images in Bibles and pamphlets that depicted the perceived enemies of Protestantism as monsters. One such woodcut showed Christ treading upon a creature with three heads: the Pope, an Ottoman, and the cherubic face of Lucifer. Here, the fears and anxieties of the Reformation are quite bluntly laid bare in the body of a monster: their opposition to the papacy; their fear of the Ottoman armies encroaching on Europe; and the all-pervasive malign influence of the Devil himself.[4] These were the forces of most concern to early Protestants, here being not only presented as inhuman and monstrous, but also vulnerable to the power of (implicitly Protestant) faith and righteousness.

As much as monsters embody all that people fear, so too does the monster-slayer embody that which they champion. We can often find the parallels between monster and monster-slayer in broadsheets and other forms of popular propaganda from the dawn of the age of print to the current day. Political cartoons are especially notorious for their use of the body of the monster and its slayer as a vehicle for their message, raising up the virtue of the monster-killer whilst denigrating and dehumanising the monstrous 'other'. One English political cartoon from 1803, for instance, sees Napoleon become a dragon whilst the Duke of Wellington takes on the role of St George, the French Emperor becoming embodiment of the 'evil other'–oppositional values to the saintly champion of England.[5] In instances such as these, politics becomes mythology, and the 'monster' becomes less than fully human. Indeed, it is not uncommon to still find political cartoons today with monsters representing more abstract concepts like the economy, or specific groups and individuals–making them both terrible and alien.

Monsters are a rich resource for historians; they are not merely set dressings but are instead actors themselves, embodying ideas that the culture that created them feared and loathed. Though especially prominent in certain source bases, such as the examples above, their enduring popularity from pre-history to the modern day sees them emerge in a wide range of materials. Historians should not, therefore, overlook them.

Thomas Wood is an independent scholar working on the history of monsters during the Reformation with a particular interest in dragons. He holds a PhD from the University of Birmingham and is the editor-in-chief of the Midlands Historical Review, an open access journal for postgraduates and early career researchers.

References and Resources:

J.R.R. Tolkien, ‘Beowulf: The Monster and The Critics’ in Proceedings of the British Academy, 22 (1936), 245-95.

J.J. Cohen, ’Monster Culture (Seven Theses)’ in J.J. Cohen (ed.), Monster Theory: Reading Culture (1996), 3-25.

Martin Luther's Monk-Calf pamphlet has been digitised as part of the Taylor Institution Library's 'Printing. Translating, Singing the Reformation' project. https://editions.mml.ox.ac.uk/editions/munchkalb/

Christ Defeats the Pope as Three-headed Beast, Magdeburg, c.1550. (https://www.loc.gov/item/2021670763/. World Digital Library).

[1] J.R.R. Tolkien, ‘Beowulf: The Monster and The Critics’ in Proceedings of the British Academy, 22 (1936), 245-95.

[2] J.J. Cohen, ’Monster Culture (Seven Theses)’ in J.J. Cohen (ed.), Monster Theory: Reading Culture (1996), 3-25.

[3] This pamphlet has been digitised as part of the Taylor Institution Library's 'Printing. Translating, Singing the Reformation' project. https://editions.mml.ox.ac.uk/editions/munchkalb/

[4] Christ Defeats the Pope as Three-headed Beast, Magdeburg, c.1550. (https://www.loc.gov/item/2021670763/. World Digital Library).

[5] Bodleian Library, Oxford, Curzon b.20(43), 'St George and the dragon (London, 1803)'.

Very interesting article highlighting how historians can think about monsters.

Though perhaps not so focused on monsters, I found Nancy Arrowsmith’s A Field Guide to the Little People worth adding to my shelves.