Petitions first appeared as a recognisable documentary form in the 1270s, during the reign of Edward I.[1]

Today, petitioning is far less labour-intensive than it was in the thirteenth century when the employment of a specialist professional scribe was required. Nowadays it is possible for people to create their own petitions and sign others online with the click of a few buttons. However, the criteria that these petitions need to meet are more demanding. To gain the attention of those in power a petition today needs 10,000 signatures before a response from the government is received and it needs 100,000 before it is considered for a debate in Parliament.[2]

In contrast to the petitions from the present day, petitions were initially ‘private petitions’. These documents were put forward by a named individual, or sometimes small groups of individuals, seeking a judicial remedy that typically only affected the petitioner/s themselves, rather than matters with broader societal implications.[3] The term ‘common petition’, by contrast, refers to petitions pertaining to the common interest of the realm. From the 1320s onwards, common petitions began to often be presented in the name of the parliamentary Commons.[4]

Petitions were not a mechanism of the common law courts; rather, they were concerned with matters that common law processes could not readily remedy.[5] The high courts of Parliament and Chancery were the major jurisdictions that dealt with petitions, which tended to be addressed to the king and chancellor respectively. The king and chancellor were both able to provide extraordinary judgement on the legal issues expressed in petitions, overriding the more rigid codes of the common law.

As well as providing access to influential jurisdiction, petitioning was also a fairly accessible route by which to seek justice. In theory, petitioning was open to any subject able to pay a fee to have their request written down.[6] This was cheap in comparison with the hierarchy of writs that had to be purchased in order to sue in common law.[7]

Medieval petitions covered a diverse range of subjects: from land disputes to retribution for violent crime; from broken marriage promises to remission for treason.

Though the subject matter of petitions varied greatly, their structure did not. Petitions were written according to a standard formula, which were dictated by the tenets of the ars dictaminis: the medieval art of prose, and in particular, epistolary prose composition.

Norton v Norton [TNA, C 1/706/40, 1532-8]. Image copyright of The National Archives. Not to be reproduced without permission.

Medieval petitions and letters shared the same set and order of five standard components established by the ars dictaminis: (1) salutatio (formal greeting to the addressee); (2) exordium (introduction); (3) narratio (narration of circumstances leading to petition); (4) petitio (presentation of request); and (5) conclusio (final part).[8]

Effective composition of a petition also required appropriate tonal reflection of the power dynamic between the petitioner and the addressee. By the second half of the fourteenth century, for instance, it was conventional for the salutatio section of petitions to Parliament to salute the king, using multiple superlative epithets.[9] The monarch was regularly referred to as the ‘most excellent’, ‘most feared’, and ‘most powerful’. Meanwhile, in the exordium section of petitions, phrases were used to signal the petitioner’s lowliness and deference in relation to their addressee: ‘your poor orator / oratrice’ and ‘beseech most humbly’ were particularly common.

Until the fifteenth century, petitions were written almost exclusively in French. Around 1420 the language of petitioning began shifting towards English, and by c.1450, English had become as dominant as French had previously been.[10]

The language of petitioning is interlinked with the fascinating relationship between petitions and vernacular literature in the late medieval period. From Chaucer onwards, writers began to use the legal form of the petition within literary texts – incorporating petitionary language or imaginary petitions within narratives, and even producing whole texts/verses structured as petitions.[11] Several different forms of literary ‘complaint’ were influenced by petitions, from the protests of peasants and Lollards to lovers’ plaints. However, the direction of influence was not necessarily just one way. Literary texts were depicting petitions in the vernacular before the legal language of petitioning shifted from French to English (Chaucer was writing imaginary vernacular petitions in the early 1300s, prior to the first recorded English language petition to Parliament). It is therefore possible that vernacular literature played a role in precipitating the major linguistic switch from French to English, as well as impacting more subtle changes to petitionary language and form.

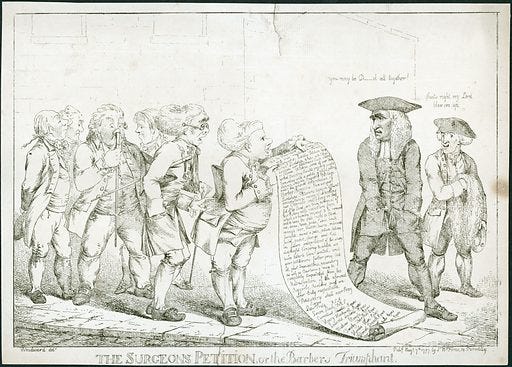

'The Surgeons Petition or The Barbers Triumphant'. Credit: Science Museum, London. (CC BY 4.0)

Beyond the medieval period, petitions became yet more influential. In early modern England, ‘the petition was a ubiquitous form of communication’ at ‘every level of society’, with petitions being produced in ‘immense numbers’.[12] In both the medieval and early modern periods, petitioning proved a particularly popular and effective way for non-elites and women to make their voices heard within the judicial and political systems.

We have access to a huge wealth of pre-modern petitions through The National Archives. For the late-medieval period, thousands of Parliament and Chancery petitions are preserved in The National Archives’ SC 8 and C 1 collections respectively.

These documents provide insight into the issues that were most important to individuals and society at large across centuries, as well as the historic role of Parliament as the country’s highest arbiter of justice.

References and Resources:

W. Scase, Literature and Complaint in England, 1272-1553 (2007)

W. M. Ormrod, G. Dodd and A. Musson (eds.) Medieval Petitions: Grace and Grievance (2009)

G. Dodd, Justice and Grace: Private Petitioning and the English Parliament in the Later Middle Ages (2007)

H. Killick, ‘The Scribes of Petitions in Late Medieval England’, in H. Killick and T. W. Smith (eds.), Petitions and Strategies of Persuasion in the Middle Ages: The English Crown and the Church, c. 1200 – c. 1550 (2018)

The Power of Petitioning in Seventeenth-Century England

Cora Wilson studied medieval and early modern history at Oxford University. Now she works on political literacy education. She is particularly interested in gender history, and loves to explore links (however tenuous!) between medieval and modern culture. You can read her work at:

[1] W. M. Ormrod, G. Dodd and A. Musson (eds.) Medieval Petitions: Grace and Grievance (2009), 7.

[2] ‘How Petitions Work’ (petition.parliament.uk).

[3] G. Dodd, Justice and Grace: Private Petitioning and the English Parliament in the Later Middle Ages (2007), 2.

[4] W. M. Ormrod, ‘Murmur, Clamour and Noise: Voicing Complaint and Remedy in Petitions to the English Crown, c.1300-c.1460’, in Ormrod, Dodd and Musson (eds.) Medieval Petitions,136.

[5] Dodd, Justice and Grace, 2.

[6] G. Dodd and S. Petit-Renaud, ‘Grace and Favour: The Petition and its Mechanisms’, in C. Fletcher, J. P., Genêt, J. Watts (eds.), Government and Political Life in England and France, c.1300-c.1500 (2015), 260.

[7] W. M. Ormrod, Women and Parliament in Later Medieval England (2020), 10.

[8] G. Dodd, ‘Writing Wrongs: The Drafting of Supplications to the Crown in Later Fourteenth-Century England’, Medium Ævum, 80/2 (2011), 222.

[9] G. Dodd, ‘Kingship, Parliament and the Court: The Emergence of “High Style” in Petitions to the English Crown, c.1350-1405’, English Historical Review, 129/538 (2014), 516.

[10] G. Dodd, ‘The Rise of English, the Decline of French: Supplications to the English Crown, c.1420-1450’, Speculum, 86/1 (2011), 118.

[11] W. Scase, Literature and Complaint in England, 1272-1553 (2007).

[12] F. Dabhoiwala, ‘Writing Petitions in Early Modern England’, in M. J. Braddick and J. Innes (eds.), Suffering and Happiness in England 1550-1850: Narratives and Representations (2017), 127.

Thanks very much for sharing!