Rate books offer an insight into the houses people lived in and the taxes they paid. They are therefore a valuable resource for local and family historians, although they are often overlooked.

It has been said that local government finance is the most boring subject in the world. But whether you are gripped by the topic or not there are plenty of records which could assist historic research. Key among them are the rate books, which record the payment of rates, a tax on the notional value of property, both domestic and business. These records have traditionally been used by house historians to identify when houses were built and who lived in them. These books are hardly ever consulted by genealogists, despite the fact that they are chock full of names and, once you are familiar with them, they are pretty easy to use.

They tell you how much the houses your forbears lived in were thought to be worth, and if several volumes are checked they can reveal when a family moved to a parish, or when a property changed hands. And if lucky you may find out what the premises were used for, who owned them (the chances are it was not the person who lived there), as well as being a useful alternative to street directories. They might even occasionally help you track down people who are not in the census for one reason or another. However, they only give the name of the person who paid the rates – generally the senior man in the household. And as the very poorest were exempt they are not always included, but the rate collectors may sometimes list them noting that they were ‘poor’ or ‘pauper’. So, if you can’t find your ancestor or a particular property it is likely that the owner was too poor to be assessed.

Originally rates had been a levy to help churches and manorial courts, but by the Reformation they were beginning to be used for non-ecclesiastical purposes. The first was to for bridges were authorised by an act of 1530 and those to pay for gaols shortly thereafter. The most important however was the poor rate, which was authorised in 1598, and a highway rate was established in 1654.[1]

In theory rates were quite a simple concept. A house might be rated at £20 per year (the supposed income derived from renting it as a single dwelling for twelve months). Every house in a parish was assigned a rental value. Commercial property could also be similarly rated. A rate was then levied at a specific number of pence or shillings in the pound. A dwelling rated at £20 might, for instance, be subject to a seven pence levy, which would mean that the householder was obliged to pay 11s 8d.

In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries determining the precise level of taxation needed at the beginning of the year could be almost impossible, particularly in urban parishes.[2] Coping with a sudden flood, for example, might overwhelm the parish’s reserves and lead to the setting of another rate. As a result, most parishes levied rates as money was required through the year. Rates would be agreed by the vestry and the fact might be recorded in the vestry minutes.[3]

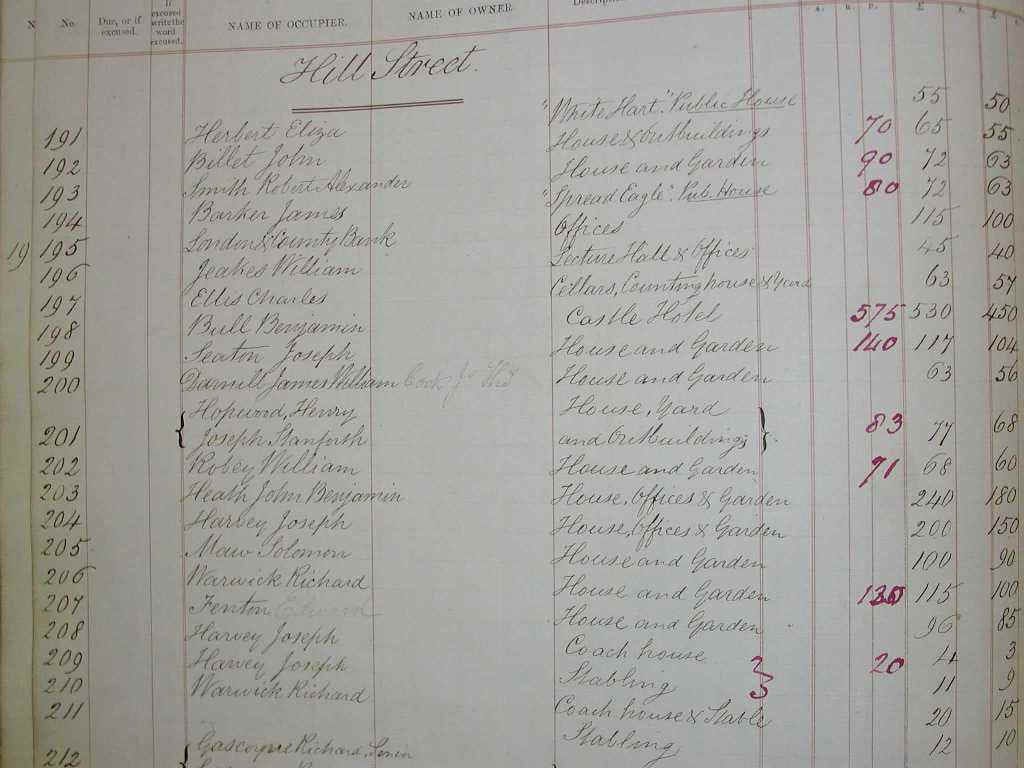

Rate book entries for Hill Street, 1860, Richmond. Richmond Local Studies Library, https://www.richmond.gov.uk/services/libraries/branch_libraries/local_studies_collection/a_walk_down_hill_street/rate_books/rate_book_entries_for_hill_street_1860

Collecting rates could be difficult. Householders either could not pay or objected to the valuation placed on their property. Appeals were head by a Justice of the Peace, who was in turn charged with overseeing the probity of process.

The most important of the rates raised was the Poor Rate which paid for the Poor Law, maintaining the workhouses, and providing pensions (out-relief) to the elderly and incapacitated. Before 1834 the Poor Rare was normally collected by parishes. Thereafter the duty was passed to poor law unions. One of the reasons why conditions in workhouses were so ghastly was because the ratepayers generally refused to authorise higher rates to improve matters. Indeed, workhouses were originally touted as being the way to keep the poor rate low. By forcing the destitute into ‘the house’ where conditions were so poor this would act as a deterrent to potential applicants and thus encourage to seek work rather than rely on the ratepayer for support.

In towns and cities, you may come across Sewer Rates, levied by Commissioners of Sewers, or Highway Rates to maintain the urban infrastructure. In rural parishes Highway Rates were used to repair local roads, usually very badly. This was a constant gripe by seventeenth and eighteenth century travellers. There were also Church Rates levied to pay for the upkeep of the parish church, which was much resented by non-conformists, who did not use the Anglican church, and it was finally abolished in 1868. In 1925 all the different types of rates were merged into one General Rate. They were replaced the Council Tax in the 1990s.

In most places rates were collected by the parish constable until the establishment of professional police forces in the mid-nineteenth century. Thereafter full or part time rate collectors were employed. They recorded payments - and arrears – in rate books, which were checked by the parish authorities. Very occasionally you may come across copies of receipts given to the householder for the payment of rates. The earliest rate books survive from the sixteenth century, but in practice they mainly begin in 1744 when ratepayers were given the right to inspect the records. There are likely to be gaps, because the books were lost, or when only a selection of volumes survive. Rate books go up to the 1960s at least, but few are publicly available.

Using the records

Rate books are kept by county and city record offices and local studies libraries. They are likely to be arranged by town or parish, and then by the district (sometimes called township or ward) assigned to the rate-collector. Most books are just for the poor rate, but if these are missing see if volumes for other types of rates survive. It is rare to find any before the eighteenth century.[4]

The earliest rate assessments were written into churchwardens and overseers account books. They usually list the householder’s name and the amount payable for his property. Or there are notebooks which were completed by the parish constable as he went from house to house. Increasingly printed books were completed by the rate collector. What they record varied from parish to parish. But they generally list the houses street by street, the value of the property, the householder’s name and the amount assessed. The name of owner of the property is also normally included where he is different to the ratepayer.

Rate books are generally arranged by street and not by the name of the ratepayer. This means that you need to know where an individual was living before you can start to use the records. On the other hand once you find them it is normally fairly easy to find them year after year, until such time as they move or die. Matters are further complicated because the books often reflect the rate collector’s route around the parish rather than the streets being in any logical order. In rural parishes finding a particular property may not present much of a problem. For urban parishes and towns there may be indexes which will indicate in which district a particular street is to be found.

When using the books it is a good idea to work back every five years or so rather than check every single year. Record the names of the occupants and the assessment for the house in question. It is also useful to note down the details of the neighbouring houses as they will help identify your house even if the occupants disappear or house numbers should change.

Until well after the Second World War most people, including the rich and well to do, lived in rented accommodation.[5] In the late nineteenth century historians estimate that only one householder in ten owned their own house. This did not change even with the arrival of the first permanent building societies in the mid-nineteenth century.

In the 1930s and 1940s, files at The National Archives show that MI5 used rate books to check up on the addresses of potential spies and enemies of the state.[6] They found these records more up to date and accurate than street directories.

Simon Fowler is a professional writer, researcher and historian. At present he is undertaking a PhD thesis in local history at Leicester University.

References and Resources:

Anthony Adolph, Tracing Your Home’s History (2006)

M. J. Daunton. ‘House Ownership from Rate Books’ Urban History Yearbook (1976)

Ida Darlington, ‘Rate Books’ in Short Guides to Records (1994)

David Iredale, Local History Research and Writing (1974)

David Reeder (ed), Archives and the Historian (1989)

W. E. Tate, The Parish Chest (1983)

Colin Thom, Researching London’s Houses (2005)

S. J. Wright, ‘Easter Books and Parish Rate Books: a new source for the urban historian’ Urban History Yearbook (1985), pp30-45

County archives may have online leaflets describing their holdings of rate books. A few local record societies may have transcribed sample rate books. They are to be found in the Bibliography of British and Irish History.

Few rate books are yet online. London Lives has a useful introduction to the subject and include abstracts from a few rate books for the late eighteenth century. www.londonlives.org/static/ParishRelief.jsp#Rates

[1] A list can be found in W. E. Tate, The Parish Chest (1983), 27-29.

[2] ‘Parish Relief’, London Lives 1690 to 1800, https://www.londonlives.org/static/ParishRelief.jsp#Rates

[3] W. E. Tate, The Parish Chest (1983), 29.

[4] Anthony Adolph, Tracing Your Home’s History (2006), 158-159.

[5] M. J. Daunton. ‘House Ownership from Rate Books’ Urban History Yearbook (1976), 24.

[6] See for example the files relating to Charles John Moody [TNA KV 2/2793-2797].