Samplers, pieces of embroidery made to practice or demonstrate needlework stitches, were a central part of a British girl’s (and sometimes a boy’s) education for approximately four hundred years. These objects, usually worked on pieces of linen with colourful silk, wool, or, later, cotton threads, were used to teach children how to sew and embroider in a variety of stitches. The vast majority of these children were middle- or upper-class girls, those whose parents could afford for them to have an education. As time went on, especially in the nineteenth century, poor girls were also given embroidery lessons. Over the centuries, samplers shifted from being stitch dictionaries, used for image and stitch reference as one worked on other embroidery projects, to artworks that displayed a young person’s accomplishments and education. These embroidered documents give us insight into lives less often found in the archive, the many girls who were taught to embroider to learn the patience, dexterity, and piety that would make them appealing potential wives and mothers.

The earliest known dated sampler made in Britain was stitched by Jane Bostocke in 1598. This sampler, stitched by Jane to commemorate the 1596 birth of her cousin Alice Lee, is in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum. The piece includes standalone motifs, a series of geometric and floral repeating patterns typical of blackwork embroidery, and an inscription reading, “ALICE LEE WAS BORNE THE 23 OF NOVEMBER BEING TWESDAY IN THE AFTER NOONE 1596.” In Jane’s sampler we see a structure and themes that appear repeatedly throughout the history of British sampler making. Jane combines word and image to illustrate a sampler’s close connection to memory, family, and even femininity.

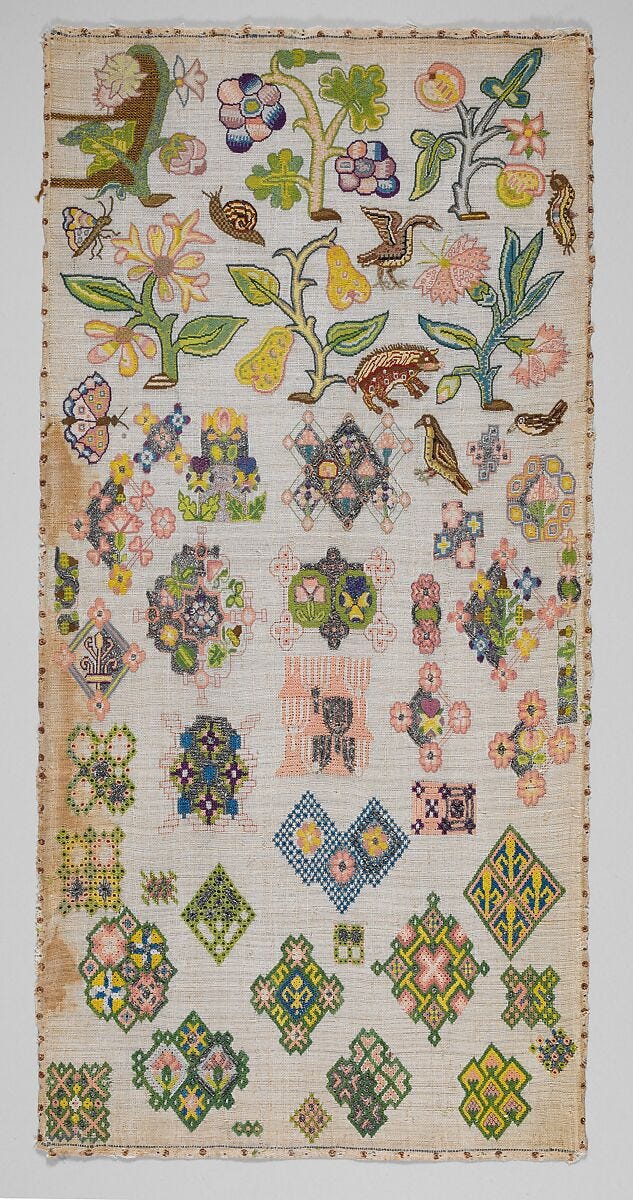

‘Spot sampler’, British, mid-17th century. Public Domain. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of Irwin Untermyer, 1964.

Sampler making in Britain was in full swing by the seventeenth century. Three types of samplers dominated: spot samplers, band samplers, and whitework samplers. Spot samplers, with their standalone floral, faunal, and geometric motifs, are thought to have come first, used to practice designs that would embellish everything from pillows to caps. Band samplers, long, thin samplers with horizontal bands of floral or geometric patterns, likely emerged in the 1630s. Scholars believe they were rolled up and unfurled when an embroiderer needed to remember a stitch or motif. Whitework samplers took the shape of band samplers, long and narrow with horizontal bands. These bands were made of whitework embroidery, needle lace, or both.

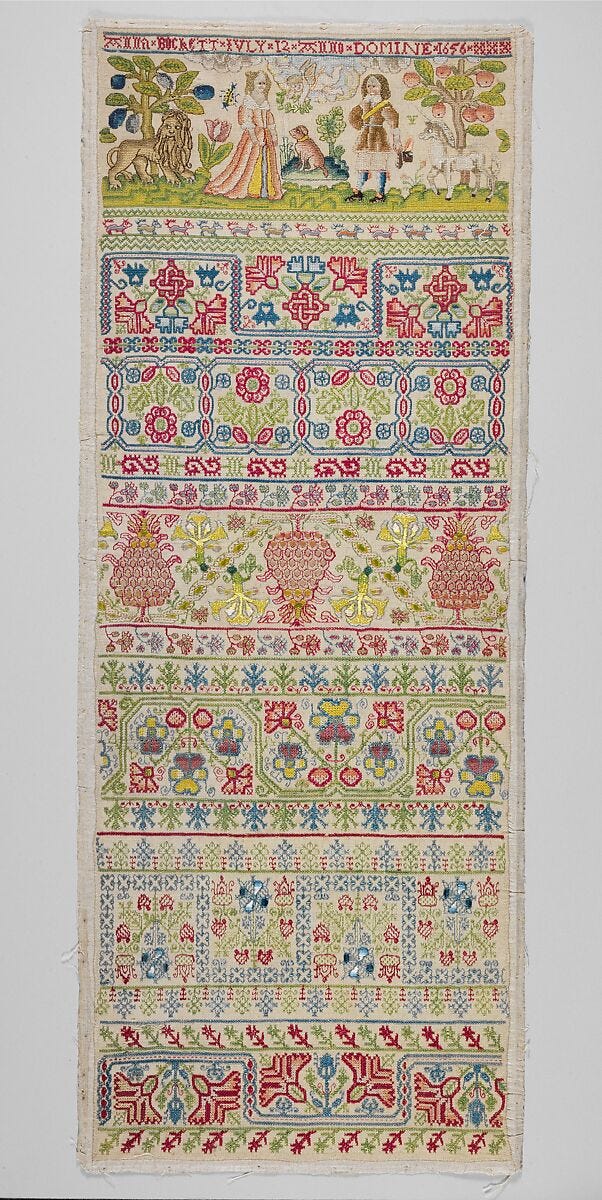

‘Band sampler’, Anna Buckett, 1656. Public Domain. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of Irwin Untermyer, 1964.

Many of these samplers were stitched by girls sent to school and were part of a larger formalised education. Samplers illustrate a growing investment in literacy in the seventeenth century; as time went on, samplers included increasing amounts of text. What were just names or initials, a date, and an alphabet in the earlier decades of band sampler making became lengthy passages of rhyming verse by the end of the century.

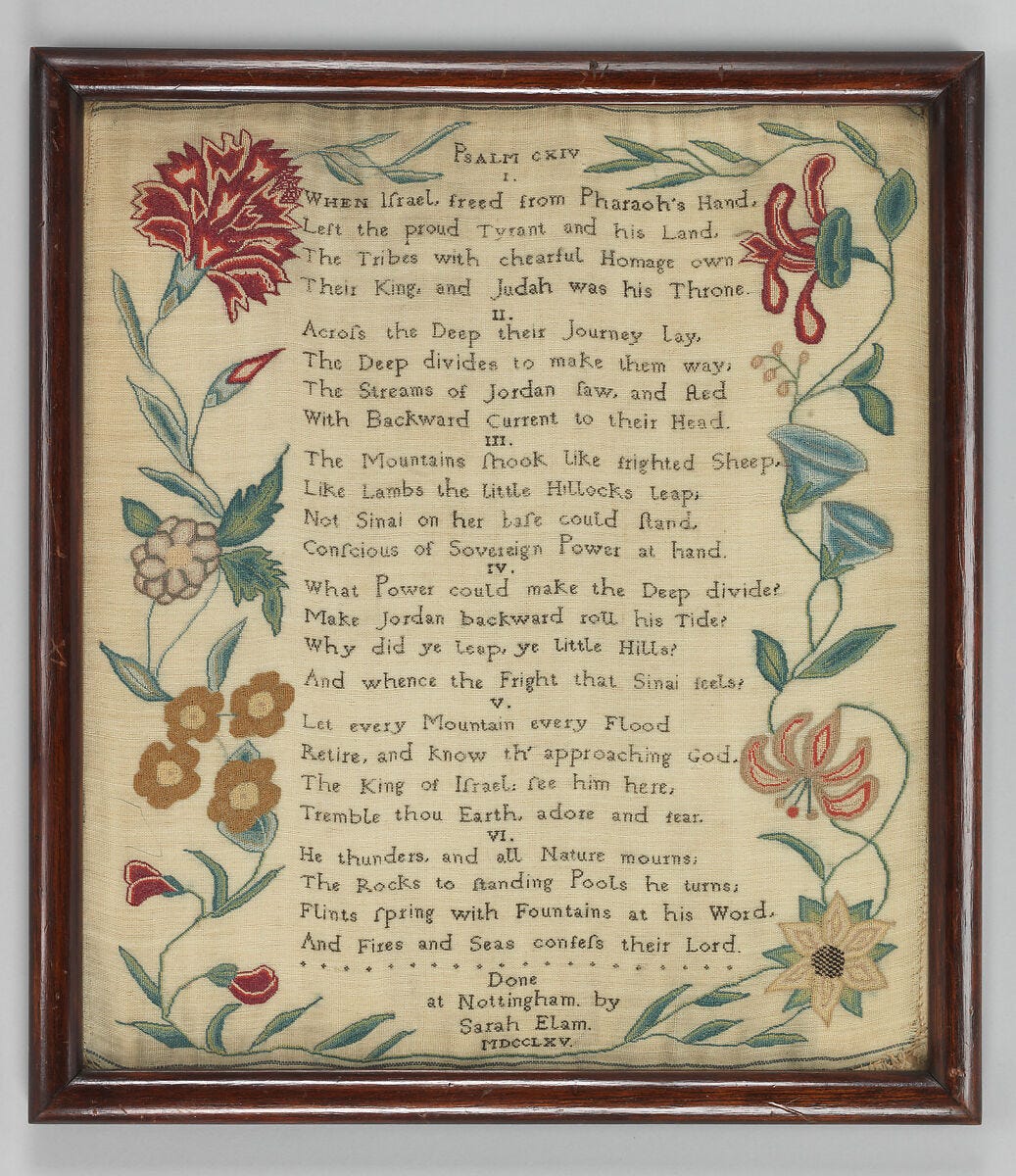

‘Sampler’, British, 1765. Public Domain. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of Elizabeth Riley, 1973.

This interest in samplers as tools of literacy continued to deepen in the eighteenth century. Samplers from the early decades of that century resembled band samplers but were shorter and, as the century progressed, had their bands of pattern replaced by bands of alphabets or rhyming, moralistic verse. Some samplers involved floral imagery, with increasing numbers of samplers involving floral tableaux or borders by the middle of the century. These were accompanied by samplers that featured idealised pastoral scenes, rife with shepherding couples in lush landscapes. At the end of the century, the types of samplers stitched by girls in school and in the home expanded to include darning and map samplers. Darning samplers allowed girls to practice the mending skills she would need as a wife, mother, and mistress of a household. Map samplers, which usually depicted various parts of the British Isles but sometimes presented continents like Europe or Asia or more personal spaces like specific parishes, taught girls needlework and geography simultaneously.

‘Embroidered darning sampler’, Frances Boyce, 1780. Public Domain. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of Elizabeth M. Riley Estate, 2002

The eighteenth century saw increased numbers of poor children and orphans receiving a formal needlework education which involved making samplers. These samplers acted as professional CVs that showed potential employers the skilful sewing and embroidery a girl could provide for a household. Some samplers or other small objects like sewing rolls (also known as hussifs), pin cushions, and watch covers were produced for sale, with the proceeds going to the charity school or orphanage. Embroidery education for poor and orphaned girls became more formalised and widespread in the nineteenth century.

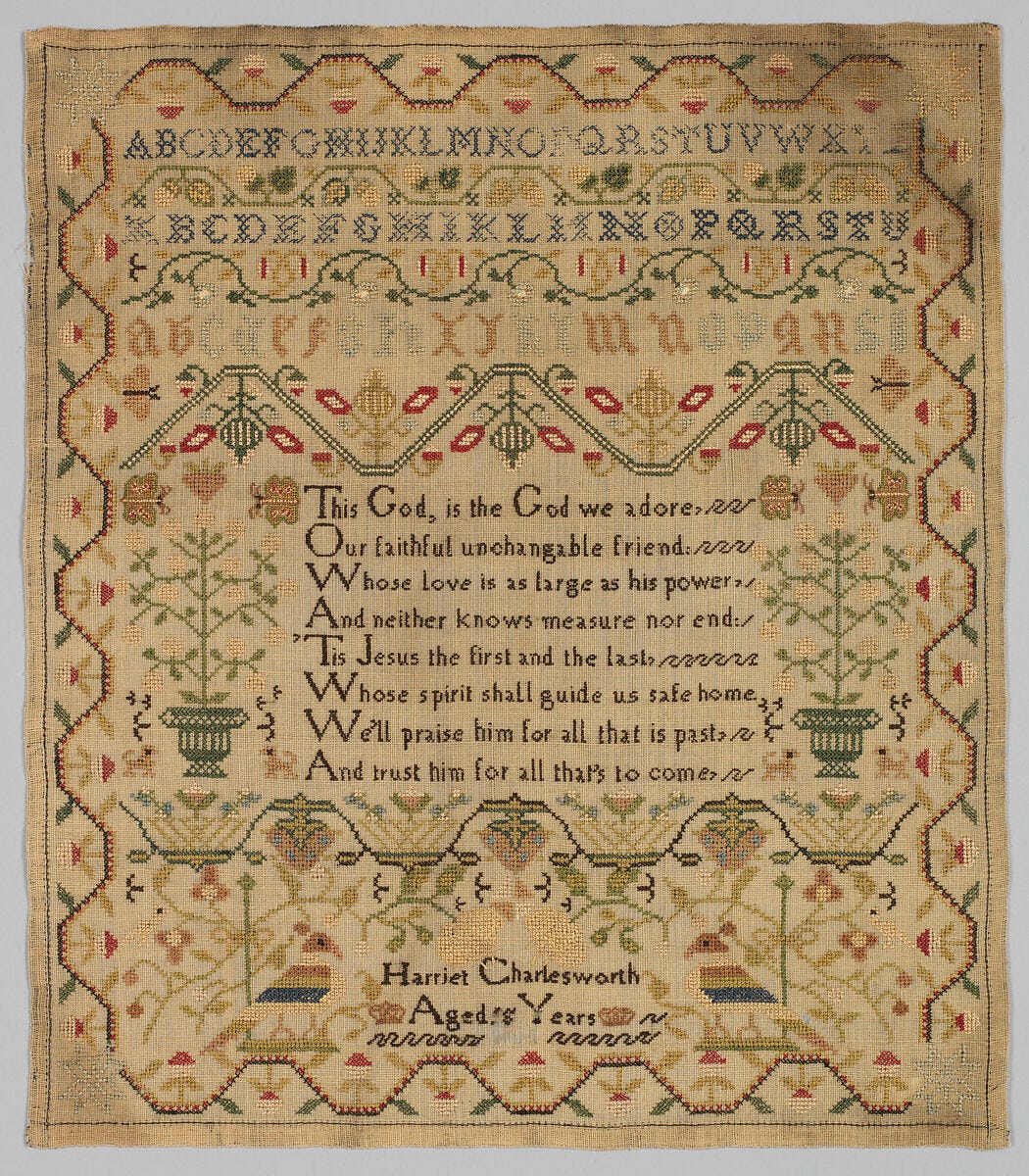

Samplers from the first several decades of the nineteenth century resemble those from the later eighteenth century, with a mixture of moralistic verse and motifs like flowers, figures, and buildings. Like many samplers from the previous decades, early nineteenth-century samplers frequently included biographical information such as a maker’s name, the year, the sampler maker’s location, and the sampler maker teacher’s name. Some samplers involved family registers or depicted families mourning for lost loved ones.

‘Sampler’, British, 19th century. Public Domain. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. From the Collection of Mrs. Lathrop Colgate Harper, Bequest of Mabel Herbert Harper, 1957.

In approximately the middle of the century, sampler making shifted to reflect the growing trend of Berlin wool work. Berlin wool work, a style of embroidery reminiscent of today’s needlepoint, involved basic stitches wrought in bright wool threads, following a printed pattern to create pixelated images. Samplers from this period include a variety of randomly placed Berlin wool worked patterns, resulting in objects that resemble the spot samplers of two hundred years earlier. By the late nineteenth century, sampler making had largely gone out of fashion. Those who were still instructed in sampler making stitched small, text-centric samplers.

Samplers are genealogical documents, so often listing information about a maker and their life. Even samplers that are unsigned or undated can tell us much about British girlhood throughout history, with indicators of what qualities girls were expected to gain through stitch and what was considered fashionable in the world of art and design. People of the past told their stories not only using pen and paper, but also a needle and thread.

Isabella Rosner is the Curator of the Royal School of Needlework and a Research Associate at Witney Antiques. She researches and cares for nearly 500 years of needlework. In 2023 she completed her PhD at King’s College London, where she studied Quaker women’s needlework, waxwork, and shellwork in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century London and Philadelphia.

References and Resources:

Clare Browne and Jennifer Wearden, Samplers from the Victoria and Albert Museum (1999)

Averil Colby, Samplers (1965)

Carol Humphrey, Sampled Lives: Samplers from the Fitzwilliam Museum (2017)

Rebecca Scott, Samplers (1997)

Embroidery – a history of needlework samplers: https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/embroidery-a-history-of-needlework-samplers

Thanks for the fascinating insight.

Living in a small semi-rural town in Yorkshire, England, the local museum centred in a 16th century town farmhouse has among its many exhibits delicately worked samplers made by, I think, 19th century girls. I'd always thought of these as a learning tool, not as a reminder of stitches and motifs. I shall pay more attention during my next visit!