Maps are a fantastic tool for the historian, adding a valuable visual aspect to our research. European maps before the advent of modern cartographical techniques were closer to artistic impressions than the precise depictions we are familiar with today. However, they offer an important sense of the main settlements and topography of an area. All maps are interpretations and so what mapmakers include is determined by the purpose of the map as well as their own, and wider, worldviews.

The earliest surviving English maps of the British Isles were drawn in the thirteen and fourteenth centuries; Matthew Paris’ map and the ‘Gough’ map. By the fifteenth century cartography was well enough understood for local surveys. The earliest comprehensive attempt at mapping England and Wales came in the late sixteenth century. Christopher Saxton made and published the first ever atlas of England and Wales in 1579 and the first wall map in 1583, following his series of county maps. Saxton’s survey was still in use until the publication of the Ordnance Survey at the end of the eighteenth century.

Saxton was a servant of Thomas Seckford, master of the Court of Requests. It was Seckford who financed the engraving and printing of these maps. Elizabeth I’s chief minister William Cecil, Lord Burghley was also an enthusiastic supporter of the project. He had a set of pre-publication proofs and annotated them as he planned for the defence of the realm against anticipated invasion. The publication of both the atlas and accompanying wall map was an unparalleled achievement in Europe at the time. Later in life Saxton was employed making estate maps for landowners across the country, especially in his native Yorkshire.

‘Westmorlandiæ et Cumberlandiæ’ in Christopher Saxton, Atlas of England [1576]. Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The finished Saxton Atlas is available digitised on the website of the Bibliothèque nationale de France: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b55007148q/f92.item.r=Saxton. Various glyphs denote different settlements and landscape features.[1]

Saxton’s maps were the basis for many other maps over the following two centuries, notably John Speed’s atlas The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine published in 1611-2. Speed was a cartographer and antiquarian who with the financial support of Sir Fulke Greville produced a series of 54 maps of the counties of England and Wales. It was published in a large folio volume that included descriptive text. He also published six maps of Scotland in 1610.

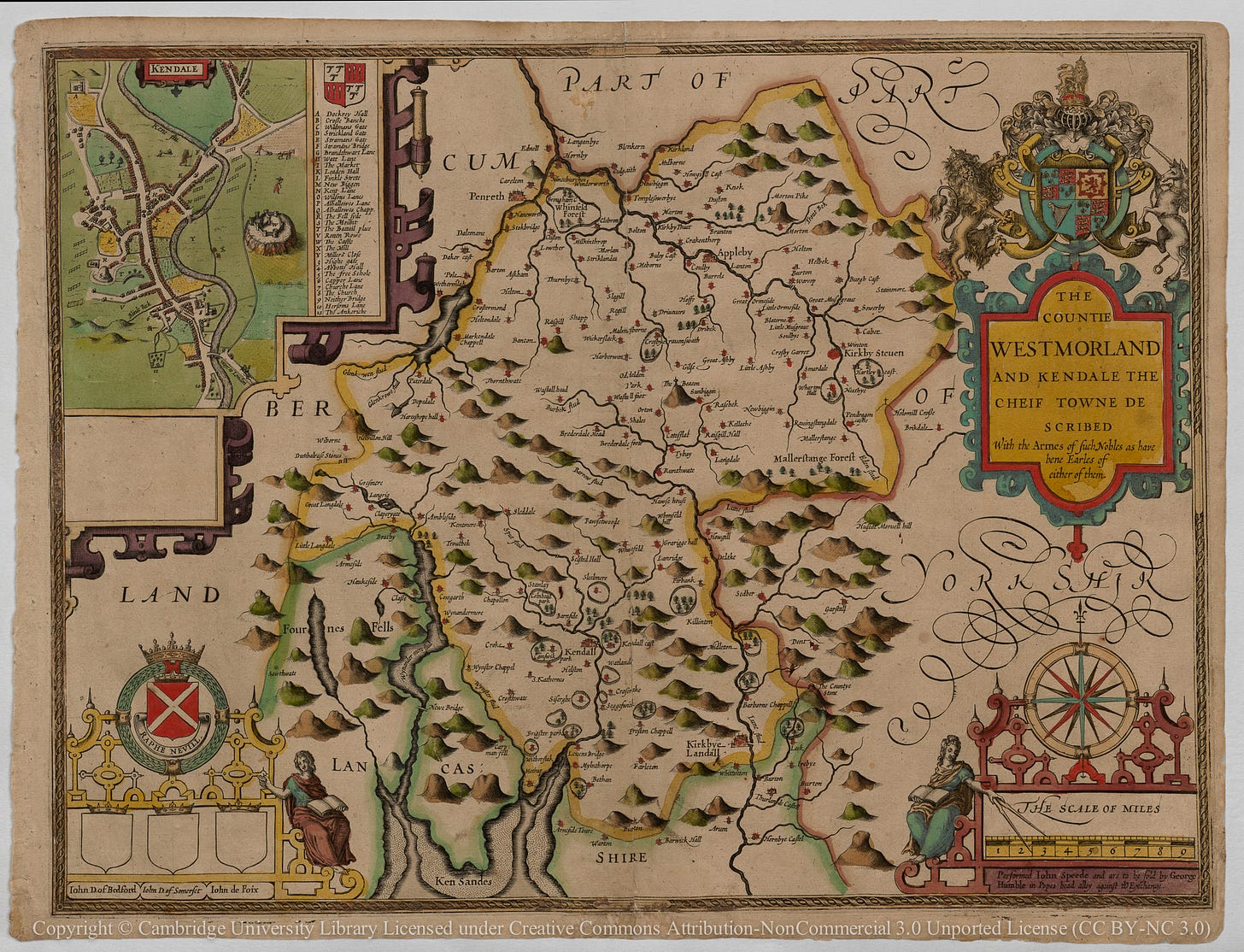

‘Westmorland’ in John Speed, The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine [1611-2]. Cambridge University Library, Atlas.2.61.1. © Cambridge University Library (CC BY-NC 3.0).

The proofs of The Theatre were printed from copper plates engraved by Jodocus Hondius in Amsterdam, then a great printing centre of Europe, before being sent back to England for checking. Speed is especially noted for his inclusion of town plans depicting many urban areas in some detail for the first time in history. Digitised copies of the proofs are available through the Cambridge University Library website http://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/PR-ATLAS-00002-00061-00001/1.

Saxton and Speed’s maps are invaluable for historians working on England and Wales in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. While these maps are objects of study in their own right, they can be used to support all kinds of research into people and places, illuminating the geography of an area and grounding research in the physical environment.

References and Resources:

Information for this post was taken from the excellent David Hey (ed.), The Oxford Companion to Local and Family History (1996), 297-9, 404, 422-3.

P. D. A. Harvey, Maps in Tudor England (1993)

I. M. Evans and H. Lawrence, Christopher Saxton: Elizabethan Map-Maker (1979)

Nigel Nicholson (ed.), The Counties of Britain by John Speed (1988)

Helen Wallis (ed.), Historian’s Guide to Early British Maps (1994)

Christopher Daniell, Atlas of Early Modern Britain, 1485-1715 (2013)

[1] A key to the glyphs is available here: Saxton/Vocabulary - Viae Regiae Wiki.

Thank you. Useful links. to find the Devon maps. Sadly Sticklepath does not appear on either map despite having an early Chantry chapel, with evidence suggesting the need for 2 priests before this date. Speculation suggests the little cob church was set back from the road and pigsties etc in front of it prevented the map makers spotting it! The vicars of Sampford Courtenay tended to forget it too except twice per year when they came the 5 miles to collect their tithes! Dissolution of the chantries under Edward VI meant they lost the priest in 1549, and I am not sure when they were re-established. Perhaps that was the reason. A drawing exists, showing it before it was burnt down and re-built in its modern form in 1875, now a Heritage Centre. http://library-cat.swheritage.org.uk/archive/p-d48309-DA144017