Twelfth Night, Epiphany, 6 January, Little Christmas, (this last one is mostly Irish) however you wish to refer to it, was in many ways a larger and more elaborate event in post-reformation Tudor England than Christmas Day itself.

The Twelve Days of Christmas were set by the Council of Tours in 567 CE. The night of the 5 or 6 January was when the Three Wise Men were said to have visited the infant Jesus. It became the best party of the year.

The day was for feasting, the type of feasting that left people so full and content that they could barely move. In 1532, it was reported that Henry VIII held a Twelfth Night banquet with over 200 dishes. Temporary kitchens had to be set up at Greenwich Palace where he was residing for the Christmas period, and they were dedicated to the making of jellies and gingerbreads among other things.[1]

Twelfth Night Cake, resembling our present-day Christmas cake, was enjoyed by many. By the late sixteenth century a tradition from the Netherlands and German-speaking countries that had been taken up by France and Spain became popular in England. A coin (Germanic) or bean (French and Spanish) was baked into the cake and the person who found it in their slice became the household king or lord for the evening. In the 1610s Ben Jonson cited ‘a great cake with a bean and pea’ as part of the Christmas celebrations. The pea was an addition representing a Queen. The bean made one a King of misrule for the night and the pea made another a Queen of misrule.[2] The tradition persisted, Samuel Pepys records a party on Epiphany night on 6 January 1660, ‘we had a brave cake brought us, and in the choosing, Pall was the Queen and Mr. Stradwick was King. After that my wife and I bid adieu and came home, it being still a great frost’.[3] Today this practice is still enacted in some households.

Twelfth Night Cake: A History of the Twelfth Night Cake

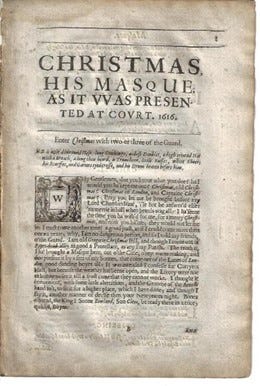

A play or some type of performance was customary on Twelfth Night at court. By the Stuart period, many were performed at the Banqueting Hall in Whitehall. Most of these were written by the playwright Ben Jonson with the sets and costumes designed by Inigo Jones the architect, who is now most famous for Queen’s House in Greenwich and Covent Garden. One of the earliest performed at Whitehall was The Masque of Blackness. This and other masques caused Puritans to react with anger and become more vocal about their dislike of Christmas celebrations, the immorality of the court and its frivolous spending.[4] One masque of note by Jonson was entitled Christmas His Masque, first performed in 1616. ‘The character of ‘Christmas’ appears in old-fashioned clothes with a long thin beard, calling himself 'old Christmas' and 'old Gregorie Christmas'. He chides the guards for refusing to let him into the party and argues that he is ‘as good a Protestant as any in my parish’ - a pointed comment at a time when Christmas celebrations were coming under attack from Puritans’.[5] Johnson's character of Christmas is an old father much as Father Christmas would later be seen as. Several of his sons and daughters appear in the play personifying traditions of the period. They include ‘Misrule’, ‘Carol’, ‘Mince Pie’, ‘Mumming’ and ‘Wassail’.

Ben Jonson, Christmas His Masque, As it was Presented at Court 1616 [c.1640]

William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, or What You Will was written around 1601 to be specifically performed on 6 January. The earliest recorded performance was presented at Middle Temple Hall on Candlemas Night, on the 2 February in 1602. The idea of inversion and reversal is present in the play, a continued theme for this time of year. It is especially evident in the roles of Viola a woman dressed as a man and Malvolio a servant who believes he has become a nobleman.

The cumulative song, The Twelve Days of Christmas dating in print from at least c.1780, demonstrates the crescendo of the Christmas period and the increase in gifts and frivolity until its climax and vast amounts of gifts. The Christmas season ended with Plough Monday, the first Monday after Epiphany and the start of the ploughing season which was a celebration in itself and is still enacted in some places.

First page of the carol From Mirth without Mischief (c. 1780). Public Domain.

References and Resources:

Ronald Hutton, The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain (2001)

A. Weir and S. Clarke, A Tudor Christmas (2018)

S. Pepys, Diary ‘Friday 6 January 1659/60’

M. Lasley, Stuart Christmas Excess at the Banqueting Hall, Whitehall

T. Moriarty, The History of Father Christmas

S. Bilton, A History of the Twelfth Night Cake | English Heritage

See also our How-to: Early Tudor Christmas - by Joe Saunders

[1] A. Weir and S. Clarke, A Tudor Christmas (2018), 122.

[2] Ronald Hutton, The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain (2001), 110.

[3] S. Pepys, Diary ‘Friday 6 January 1659/60’.

[4] For more on this masque and the reactions to it see: M. Lasley, Stuart Christmas Excess at the Banqueting Hall, Whitehall.

[5] T. Moriarty, The History of Father Christmas.