Sheriff’s Bills of Cravings

England

Sheriff’s bills of cravings are the annual claims for reimbursement of money that a sheriff spent during their appointment. These bills do not belong to the sheriffs of the modern imagination, from wild west films and tv shows. Instead, they belong to legal officials who were responsible for a shire. The most well-known in popular culture is perhaps the Sheriff of Nottingham from the Robin Hood tales. The word sheriff is a contraction of ‘shire reeve’ (Old English scírgeréfa and Middle English scyrreve) and the Oxford English Dictionary traces the words to at least c.1034.[1] Before the Norman Conquest the sheriff represented royal authority, presiding over the shire-moot and upholding the law and administration of the royal demesne.

The role of a sheriff continued after the Conquest although many of their responsibilities changed, and they ended up less powerful than Justices of the Peace, holding roles more akin to policing. Many famous people in the early modern period had connections to sheriffs. John Evelyn noted in his diary on 3 November 1633, ‘this yeare was my Father made sheriff the last (as I thinke) who served in that honorable office for Surrey & Sussex befor they were disjoyned’.[2] In Pepys’s diary, there are accounts of him going for dinner with his friend who was the sheriff and visiting a friend who would be sheriff in the next year.[3]

Louis Rhead, Bold Robin Hood and His Outlaw Band: Their, Exploits in Sherwood Forest (1912), 129. © Public Domain

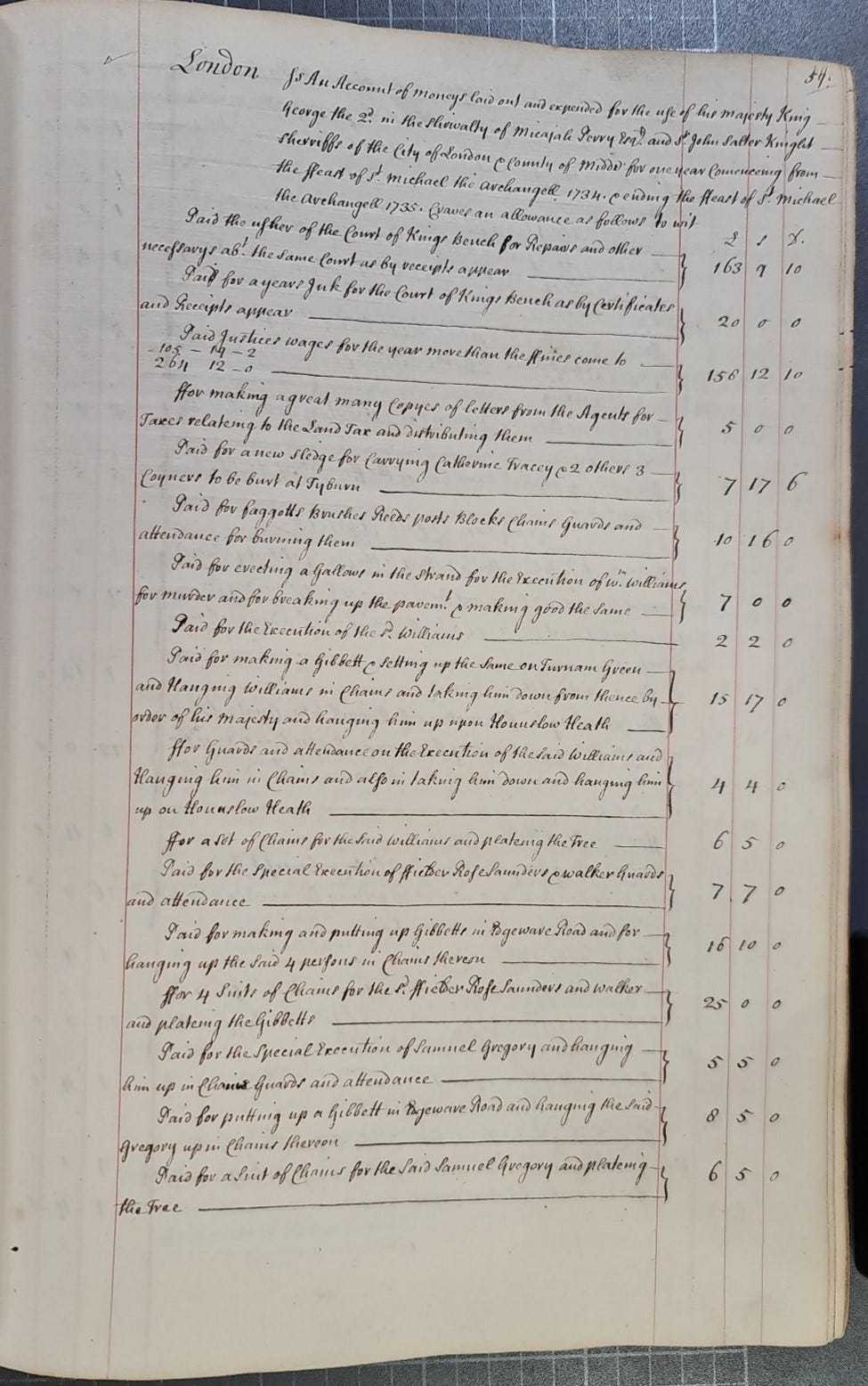

Cravings are a fascinating source of information. Sheriffs often ran county gaols and as such kept records of individuals confined there. Maintaining prisoners before trials, execution expenses, and escorting prisoners to transportation and into prison hulks, all appear in the cravings. They claim amounts for carrying out whippings, and as the historian Simon Devereaux noted, ‘systematic review of these records suggests much about the changing character and proportion of public, physical punishments in Hanoverian England, as the sheriffs were obliged to distinguish between the amount claimed for a ‘common’ whipping and that claimed for a whipping ‘at the cart’s tail’ along a specified route’. Until 1779 £1 could be claimed for ‘common’ and £2 for ‘cart’s tail’ whippings, they were thereafter tripled to £3 and £6.[4] The costs for gibbeting individuals after their executions are also in the cravings. The average gibbet cost £16 but some cost more than £50.[5] It was an expensive practice, and the cravings show the cost incurred from hiring the smiths to measure an individual criminal while alive, so they fit their gibbets perfectly, to the erection and transportation of a body to a gibbet site and the security needed while the act was performed.

Sheriffs' cravings, 1735-1739. TNA, T 90/147. With kind permission of The National Archives.

If a craving was signed by the Chancellor, the reimbursement was secured. Sometimes claims were made by widows or children of a deceased sheriff. Sheriffs’ cravings are a neglected source in many ways, only recently receiving attention from scholars. Maybe because they are stored ‘in the Treasury records rather than in the court archives and had therefore been missed by most criminal justice historians’.[6]

The records do not systematically inform researchers on ages, occupations, nor other details of an offender but occasional glimpses are possible, and as the reimbursements were produced annually by the Exchequer of the Treasury in London, they can easily be cross referenced with Assize records.

The cravings are mostly housed at The National Archives at Kew in a subseries within E 197. Three books cover 1724-1733, and 1800-1806. The original bills for the years 1746 to 1785 are in T 64. The entry books 1733-1822 are in T 90 and for 1823 to 1959 in T 20.[7] They are indexed by shrievalty. Up until 1849 all books were examined by the Exchequer Seal Office, and some contain the reports from this office. Local tradesmen and some newspaper advertisements have been inserted into these books for reference as well.

The 1887 Sheriff’s Act can be viewed in its entirety online here. Today, a sheriff or high sheriff is merely a ceremonial county or city official.

Further References and Resources:

J. McGovern, The Tudor Sheriff: A Study in Early Modern Administration (2021)

Myron C. Noonkester, ‘Power of the County: Sheriffs and Violence in Early Modern England’ in J. P. Ward, ed., Violence, Politics, and Gender in Early Modern England (2008)

For more on gibbets and Sheriffs Cravings see: S. Tarlow, The Golden and Ghoulish Age of the Gibbet in Britain (2017) which is open access.

[1] "Sheriff, n." OED Online, www.oed.com/view/Entry/178002. Accessed 1 October 2022.

[2] J. Evelyn, The Diary of John Evelyn [G. de la Bédoyère, ed.] (2004), 23.

[3] All references to Sheriffs in Samuel Pepys’s Diary can be searched here.

[4] S. Devereaux, ‘The Abolition of the Burning of Women in England Reconsidered’ Crime, History & Societies, Vol. 9, No. 2 (2005), 83.

[5] P. King, Punishing the Criminal Corpse, 1700-1840 Aggravated Forms of the Death Penalty in England (2017), 101.

[6] King, Punishing the Criminal Corpse, 80.

[7] Bills of Sheriff’s Cravings | The National Archives. Accessed 1 October 2022.